Abstract

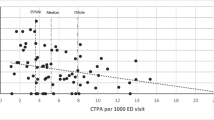

We examined the patient and physician characteristics related to the use and yield of computed tomography pulmonary angiogram (CTPA) for the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism (PE) at a tertiary academic hospital emergency department (ED). A cross-sectional retrospective study was conducted on 835 consecutive ED patients with suspected PE who underwent CTPA. Radiology report data were extracted from our institution’s RIS PACS software (Syngo Imaging, Siemens) based on a targeted search of all CTPA reports from 2010 to 2012. Utilization and PE positivity rates of CTPA were calculated and correlated with patient characteristics including age and gender, as well as emergency physician (EP) characteristics including gender, years in practice, and training certification. Acute PE was diagnosed in 17.8 % of patients. A further 32.9 % of the scans were negative for PE but had other clinically significant findings. We found higher utilization rates in female and older patients (p < 0.001), however, without corresponding differences in PE positivity rates compared to their male and younger counterparts. There was a high inter-physician variation in CTPA utilization rate (range 0.21–0.77 scans per 100 patients seen) and PE positivity rate (range 6.7–38.9 %). However, neither rates correlated with EP years of experience (p > 0.15 with cut-offs at 5, 10, and 20 years post-residency), gender (p = 0.59), or training certification (p = 0.56 between EPs certified by the 5-year program of the Royal College of Physicians of Canada versus the 3-year program of the College of Family Physicians of Canada). Our study demonstrated considerable inter-physician variability in the utilization and PE positivity rates of CTPA. These results suggest an opportunity for a more standardized approach to the use of CTPA among EPs at our institution.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Smith-Bindman R et al (2012) Use of diagnostic imaging studies and associated radiation exposure for patients enrolled in large integrated health care systems, 1996–2010. JAMA J Am Med Assoc 307:2400–2409

Perrier A et al (2005) Multidetector-row computed tomography in suspected pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med 352:1760–1768

Moores LK, Jackson WL Jr, Shorr AF, Jackson JL (2004) Meta-analysis: Outcomes in patients with suspected pulmonary embolism managed with computed tomographic pulmonary angiography. Ann Intern Med 141:866–874

Blachere H et al (2000) Pulmonary embolism revealed on helical CT angiography: Comparison with ventilation-perfusion radionuclide lung scanning. AJR Am J Roentgenol 174:1041–1047

Anderson DR et al (2007) Computed tomographic pulmonary angiography vs. ventilation-perfusion lung scanning in patients with suspected pulmonary embolism: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA J Am Med Assoc 298:2743–2753

Stein PD et al (2006) Multidetector computed tomography for acute pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med 354:2317–2327

Schissler AJ et al (2013) CT pulmonary angiography: Increasingly diagnosing less severe pulmonary emboli. PLoS ONE 8:e65669

Donohoo JH, Mayo-Smith WW, Pezzullo JA, Egglin TK (2008) Utilization patterns and diagnostic yield of 3421 consecutive multidetector row computed tomography pulmonary angiograms in a busy emergency department. J Comput Assist Tomogr 32:421–425

Kuroki M et al (2006) Incidence of pulmonary embolism in younger versus older patients using CT. J Thorac Imaging 21:167–171

Groth M et al (2012) Age-related incidence of pulmonary embolism and additional pathologic findings detected by computed tomography pulmonary angiography. Eur J Radiol 81:1913–1916

Costa AF, Basseri H, Sheikh A, Stiell I, Dennie C (2013) The yield of CT pulmonary angiograms to exclude acute pulmonary embolism. Emerg Radiol. doi:10.1007/s10140-013-1169-x

Sood R, Sood A, Ghosh AK (2007) Non-evidence-based variables affecting physicians’ test-ordering tendencies: a systematic review. Neth J Med 65:167–177

Raja AS et al (2012) Effect of computerized clinical decision support on the use and yield of CT pulmonary angiography in the emergency department. Radiology 262:468–474

Chandra S, Sarkar PK, Chandra D, Ginsberg NE, Cohen RI (2013) Finding an alternative diagnosis does not justify increased use of CT-pulmonary angiography. BMC Pulm Med 13:9

Brown MD, Vance SJ, Kline JA (2005) An emergency department guideline for the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism: an outcome study. Acad Emerg Med Off J Soc Acad Emerg Med 12:20–25

Hall WB et al (2009) The prevalence of clinically relevant incidental findings on chest computed tomographic angiograms ordered to diagnose pulmonary embolism. Arch Intern Med 169:1961–1965

Adams DM (2013) Adherence to PIOPED II investigators’ recommendations for computed tomography pulmonary angiography. Am J Med 126:36–42

Mamlouk MD et al (2010) Pulmonary embolism at CT angiography: Implications for appropriateness, cost, and radiation exposure in 2003 patients. Radiology 256:625–632

Richman PB et al (2004) Prevalence and significance of nonthromboembolic findings on chest computed tomography angiography performed to rule out pulmonary embolism: a multicenter study of 1,025 emergency department patients. Acad Emerg Med Off J Soc Acad Emerg Med 11:642–647

Lombard J, Bhatia R, Sala E (2003) Spiral computed tomographic pulmonary angiography for investigating suspected pulmonary embolism: Clinical outcomes. Can Assoc Radiol J Assoc Can Radiol 54:147–151

Prologo JD, Gilkeson RC, Diaz M, Asaad J (2004) CT pulmonary angiography: a comparative analysis of the utilization patterns in emergency department and hospitalized patients between 1998 and 2003. AJR Am J Roentgenol 183:1093–1096

Parker MS et al (2005) Female breast radiation exposure during CT pulmonary angiography. AJR Am J Roentgenol 185:1228–1233

Hurwitz LM et al (2007) Radiation dose from contemporary cardiothoracic multidetector CT protocols with an anthropomorphic female phantom: Implications for cancer induction. Radiology 245:742–750

Pijpe A et al (2012) Exposure to diagnostic radiation and risk of breast cancer among carriers of BRCA1/2 mutations: Retrospective cohort study (GENE-RAD-RISK). BMJ 345:e5660

Larson DB, Johnson LW, Schnell BM, Salisbury SR, Forman HP (2011) National trends in CT use in the emergency department: 1995–2007. Radiology 258:164–173

Wiener RS, Schwartz LM, Woloshin S (2011) Time trends in pulmonary embolism in the United States: Evidence of overdiagnosis. Arch Intern Med 171:831–837

Rosen MP, Davis RB, Lesky LG (1997) Utilization of outpatient diagnostic imaging. Does the physician’s gender play a role? J Gen Intern Med 12:407–411

Lautenschlager NT, Förstl H (2007) Personality change in old age. Curr Opin Psychiatry 20:62–66

Schertler T et al (2009) Triple rule-out CT in patients with suspicion of acute pulmonary embolism: Findings and accuracy. Acad Radiol 16:708–717

Tsai K-L, Gupta E, Haramati LB (2004) Pulmonary atelectasis: a frequent alternative diagnosis in patients undergoing CT-PA for suspected pulmonary embolism. Emerg Radiol 10:282–286

Wells PS et al (2001) Excluding pulmonary embolism at the bedside without diagnostic imaging: Management of patients with suspected pulmonary embolism presenting to the emergency department by using a simple clinical model and d-dimer. Ann Intern Med 135:98–107

Stiell IG et al (1997) Variation in ED use of computed tomography for patients with minor head injury. Ann Emerg Med 30:14–22

Prevedello LM et al (2012) Variation in use of head computed tomography by emergency physicians. Am J Med 125:356–364

Mehrotra A et al (2012) Physicians with the least experience have higher cost profiles than do physicians with the most experience. Health Aff Proj Hope 31:2453–2463

Charlson ME, Karnik J, Wong M, McCulloch CE, Hollenberg JP (2005) Does experience matter? A comparison of the practice of attendings and residents. J Gen Intern Med 20:497–503

Maserejian NN et al (2014) Variations among primary care physicians in exercise advice, imaging, and analgesics for musculoskeletal pain: Results from a factorial experiment. Arthritis Care Res 66:147–156

Scholer SJ, Pituch K, Orr DP, Clark D, Dittus RS (1996) Effect of health care system factors on test ordering. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 150:1154–1159

Ferrier BM, Woodward CA, Cohen M, Williams AP (1996) Clinical practice guidelines. New-to-practice family physicians’ attitudes. Can Fam Physician Médecin Fam Can 42:463–468

Moore K, Lucky CA (1999) Emergency medicine training in Canada. CJEM 1:51–53

Ducharme J, Innes G (1997) The FRCPC vs. the CCFP(EM): is there a difference 10 years after residency? CAEP Commun Fall 1–4

Schattner A (2012) Test appropriateness index. Am J Med 125:e13

Kassirer JP (1989) Our stubborn quest for diagnostic certainty. A cause of excessive testing. N Engl J Med 320:1489–1491

Lucassen W et al (2011) Clinical decision rules for excluding pulmonary embolism: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 155:448–460

Rodger MA, Maser E, Stiell I, Howley HEA, Wells PS (2005) The interobserver reliability of pretest probability assessment in patients with suspected pulmonary embolism. Thromb Res 116:101–107

Chunilal SD, Eikelboom JW, Attia J et al (2003) Does this patient have pulmonary embolism? JAMA 290:2849–2858

Garg K, Sieler H, Welsh CH, Johnston RJ, Russ PD (1999) Clinical validity of helical CT being interpreted as negative for pulmonary embolism: Implications for patient treatment. AJR Am J Roentgenol 172:1627–1631

Donato AA, Scheirer JJ, Atwell MS, Gramp J, Duszak R Jr (2003) Clinical outcomes in patients with suspected acute pulmonary embolism and negative helical computed tomographic results in whom anticoagulation was withheld. Arch Intern Med 163:2033–2038

Swensen SJ et al (2002) Outcomes after withholding anticoagulation from patients with suspected acute pulmonary embolism and negative computed tomographic findings: a cohort study. Mayo Clin Proc 77:130–138

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mr. Andrew McLeod for his assistance with retrieving and providing institutional epidemiological data.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Y.A., Gray, B., Bandiera, G. et al. Variation in the utilization and positivity rates of CT pulmonary angiography among emergency physicians at a tertiary academic emergency department. Emerg Radiol 22, 221–229 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10140-014-1265-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10140-014-1265-6