Abstract

Background:

The primary aim was to use routine data to compare cancer diagnostic intervals before and after implementation of the 2005 NICE Referral Guidelines for Suspected Cancer. The secondary aim was to compare change in diagnostic intervals across different categories of presenting symptoms.

Methods:

Using data from the General Practice Research Database, we analysed patients with one of 15 cancers diagnosed in either 2001–2002 or 2007–2008. Putative symptom lists for each cancer were classified into whether or not they qualified for urgent referral under NICE guidelines. Diagnostic interval (duration from first presented symptom to date of diagnosis in primary care records) was compared between the two cohorts.

Results:

In total, 37 588 patients had a new diagnosis of cancer and of these 20 535 (54.6%) had a recorded symptom in the year prior to diagnosis and were included in the analysis. The overall mean diagnostic interval fell by 5.4 days (95% CI: 2.4–8.5; P<0.001) between 2001–2002 and 2007–2008. There was evidence of significant reductions for the following cancers: (mean, 95% confidence interval) kidney (20.4 days, −0.5 to 41.5; P=0.05), head and neck (21.2 days, 0.2–41.6; P=0.04), bladder (16.4 days, 6.6–26.5; P⩽0.001), colorectal (9.0 days, 3.2–14.8; P=0.002), oesophageal (13.1 days, 3.0–24.1; P=0.006) and pancreatic (12.6 days, 0.2–24.6; P=0.04). Patients who presented with NICE-qualifying symptoms had shorter diagnostic intervals than those who did not (all cancers in both cohorts). For the 2007–2008 cohort, the cancers with the shortest median diagnostic intervals were breast (26 days) and testicular (44 days); the highest were myeloma (156 days) and lung (112 days). The values for the 90th centiles of the distributions remain very high for some cancers. Tests of interaction provided little evidence of differences in change in mean diagnostic intervals between those who did and did not present with symptoms specifically cited in the NICE Guideline as requiring urgent referral.

Conclusion:

We suggest that the implementation of the 2005 NICE Guidelines may have contributed to this reduction in diagnostic intervals between 2001–2002 and 2007–2008. There remains considerable scope to achieve more timely cancer diagnosis, with the ultimate aim of improving cancer outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Earlier diagnosis of cancer is increasingly acknowledged as a key element of the drive to improve cancer outcomes (Department of Health, 2011). An estimated 5–10 000 deaths within 5 years of diagnosis could be avoided annually in England if efforts to promote earlier diagnosis and appropriate primary surgical treatment are successful (Abdel-Rahman et al, 2009) and a National Awareness and Early Diagnosis Initiative (NAEDI) is addressing this challenge (Richards, 2009). Elsewhere in Europe, similar objectives are being pursued by a variety of national initiatives (Olesen et al, 2009).

One of the key phases in the journey for people with symptoms who go on to develop cancer is the ‘diagnostic interval’. This is the period between the first presentation of potential cancer symptoms (usually to primary care) and diagnosis (Hamilton, 2010; Weller et al, 2012). By contributing to shorter overall times to diagnosis, shorter diagnostic intervals should lead to earlier stage diagnoses and better cancer outcomes (Richards et al, 1999; Tørring et al, 2011), although the body of evidence to support this hypothesis remains limited (Neal, 2009). Expediting the assessment of patients with suspected cancer has been a priority for the UK Government since 1997 (Department of Health, 1997). An urgent referral pathway for suspected breast cancer was introduced in 1999 and for all other cancers in 2000. Following the publication in 2005 of NICE guidance on urgent referral for suspected cancer (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2005), this pathway attained a new prominence because Primary Care Trusts were monitored by the Healthcare Commission on their implementation of NICE guidance. Urgent referral rates rose from approximately 350 out of 100 000 to 1900 out of 100 000 between 2004 and 2010 (Leeds North West PCT, 2005; National Cancer Information Network, 2011).The Cancer Reform Strategy (Department of Health, 2007) introduced a strong policy focus on earlier diagnosis of cancer and resulted in the NAEDI (http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/cancer-info/spotcancerearly/naedi/). This included work in general practice, including a national audit of cancer diagnosis in primary care in 2009/2010 (Rubin et al, 2011). A wide-ranging programme of engagement with primary care has developed, from improving consultation skills and decision support to practice cancer profiles (http://ncat.nhs.uk/our-work/diagnosing-cancer-earlier/gps-and-primary-care#). Other initiatives intended to shorten the diagnostic interval have included additional resources to improve access to diagnostic tests.

Measuring diagnostic intervals is important because it allows temporal and international comparisons, and may identify cancers where specific interventions to expedite diagnosis could be targeted, since diagnostic pathways vary greatly between cancers (Allgar and Neal, 2005). It can complement recent insights into the number of GP consultations prior to referral to provide a more complete picture of the diagnostic process (Lyratzopoulos et al, 2012). Measurement of diagnostic intervals is also necessary to determine the effect of those NAEDI interventions directed at the primary care part of the pathway to diagnosis.

Primary care data sets offer an important resource in the study of cancer diagnostic pathways. These data sets have previously been used to determine the positive predictive value of symptoms for cancer (Jones et al, 2007; Dommett et al, 2012) and to construct clinical decision support tools (Hamilton, 2009; Hippisley-Cox and Coupland, 2012). The primary aim of this study was to use routinely collected data to compare diagnostic intervals between two cancer cohorts, defined before and after the implementation of the 2005 NICE Referral Guidelines for Suspected Cancer. Secondary aims were to compare diagnostic intervals across cancers, and across different presenting symptoms.

Materials and methods

Data set

The General Practice Research Database (GPRD, but now the Clinical Practice Research Datalink – CPRD) is the world’s largest computerised database of anonymised longitudinal medical records from primary care. These records include details of all consultations and diagnoses. We used the following patient inclusion criteria:

-

A new record of a primary diagnosis of 15 types of incident cancer (breast, lung, colorectal, gastric, oesophageal, pancreatic, kidney, bladder, testicular, cervical, endometrial, leukaemia, myeloma, lymphoma, and head and neck) in the study period. Three cancers (ovarian, brain, and prostatic) of the 18 adult cancers with the highest incidence were not studied because the data set was also being used to identify and quantify the risks of cancer with each cancer site, and these three sites had been previously studied for that purpose. Hence, diagnostic intervals for these three cancers were not studied.

-

At least 1 year of complete GPRD records before diagnosis.

-

Aged ⩾40 years at diagnosis. Younger patients were not included because of the rarity of cancer diagnoses in this group. This is in keeping with many similar primary care studies (e.g. Hamilton, 2009).

The first entry of a code pertaining to the cancer diagnosis was taken as the date of diagnosis and the clinical record for the 12-month period preceding this date was studied.

Patient cohorts

Two cohorts of patients were compared. Cohort 1 consisted of patients diagnosed between 01 January 2001 and 31 December 2002 inclusive, and Cohort 2 between 01 January 2007 and 31 December 2008 inclusive. These cohorts were chosen to allow sufficient time before and after the publication and implementation of the 2005 NICE Referral Guidelines for Suspected Cancer.

Symptom codes

A list of potential symptoms for each cancer was developed and agreed between RDN, GR, and WH, all practising clinicians. The principles adopted were as follows:

-

Symptoms were those of primary local and regional disease, not metastatic or recurrent disease.

-

Symptoms with a published independent association with cancer, and carrying a risk of >0.5% for a patient presenting to primary care, based upon:

-

systematic review evidence from primary care studies, or mixed primary/secondary care where primary care studies could be easily identified, or

-

single primary care studies using rigorous methods of the above, or

-

consensus statements.

-

These symptom lists were categorised as ‘site-specific symptoms’. In addition, ‘non-specific’ symptoms, potentially caused by any cancer, were agreed, again with reference to the literature. These were: anaemia, anorexia, fatigue, and weight loss. These four symptoms were used in the analyses for all 15 cancers, along with their corresponding site specific symptoms. The full list of symptoms and further detail on applying codes to the data set and validation of identifying codes are shown in Appendix 1.

NICE-qualifying symptoms

We classified all symptoms according to whether they were ‘NICE-qualifying symptoms’ or not. NICE-qualifying symptoms were those specifically cited in the NICE Guideline for Urgent Referral of Suspected Cancer as requiring urgent referral for either investigation or specialist assessment (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2005). To do this, the three clinical researchers (GR, WH, and RDN) independently classified the list of symptoms for each cancer; these were compared and consensus reached. A number of assumptions had to be made in this process. These, along with the final lists are shown in Appendix 2.

Diagnostic intervals

The ‘diagnostic interval’ was defined as the duration from the first occurrence of a symptom code in GPRD to the date of cancer diagnosis. The date of diagnosis was defined as the first entry of the code pertaining to a cancer diagnosis in the primary care record, in exactly the same way as many other studies of primary care diagnosis (e.g. Hamilton, 2009). We analysed data for 1 year before diagnosis. Although there have been reports of patients experiencing symptoms for more than a year before diagnosis (Corner et al, 2005), it is difficult to know whether the very early symptoms genuinely arise from the cancer, as many cancer symptoms may also arise from benign or incidental conditions. In the CAPER studies, no symptom was reliably more common in cases than controls more than a year before diagnosis in colorectal, lung or prostate cancers (Hamilton, 2009). Thus we chose 1 year as a reasonable compromise, to minimise the risk of our mislabelling a symptom actually unrelated to the cancer as being the index symptom. Our definitions and methods are in keeping with recently published recommendations (Weller et al, 2012).

Data analysis

Mean (s.d.) patient age and the percentage of females are reported for each cancer type within each cohort. For each cancer–cohort combination, the percentages of patients who had any identifiable symptom code during the year prior to diagnosis are presented. Diagnostic interval was calculated only for those patients who had identifiable symptom codes. For each cancer–cohort combination, the distribution of diagnostic interval was summarised for first symptomatic presentation, reporting the mean, standard deviation, median, inter-quartile range (IQR), and 90th centile. Median, IQR, and 90th centiles are shown as the preferred method for describing these skewed data but the t-test was used to compare the mean diagnostic intervals between Cohort 1 (2001–2002) and Cohort 2 (2007–2008), both overall and for each cancer type, as we wanted to make inferences about the mean change. Therefore, the mean and standard deviation for each cohort are also shown (Thompson and Barber, 2000). Because the diagnostic interval distributions were skewed, we validated the t-test results by constructing bias corrected accelerated bootstrap confidence intervals for the mean difference as these are robust to non-Normality (Davison and Hinkley, 1997). As the bootstrap confidence intervals were virtually the same as the t-test confidence intervals, we report results from the latter analysis since it also provides P-values. Linear regression was used to carry out tests of interaction to compare the mean change in diagnostic interval between presentations of a NICE-qualifying symptom alone or in combination (‘NICE’) and presentations of a non-NICE-qualifying symptom (‘not NICE’). These regression models included as predictor variables cohort status, NICE category status, and the interaction between cohort status and NICE category status. The P-value for the interaction term was used to quantify evidence that the change in mean diagnostic interval differs between NICE and non-NICE categories. All data manipulation and analyses were performed using Stata software version 10.

Results

Demographic characteristics and proportions of patients with recorded symptoms

In total, 37 588 patients had a new diagnosis of cancer (Cohort 1 – 15 906 and Cohort 2 – 21 682), and of these 20 535 (54.6%) had a recorded symptom in the year prior to diagnosis and were included in the analysis (Cohort 1 – 8181 and Cohort 2 – 12 354). The age and gender of the patients as well as the percentage with symptoms for each cancer group are summarised separately for the two cohorts (2001–2002 and 2007–2008) in Table 1. The mean ages of patients in the two cohorts were similar for all cancers. Because the data set only contained patients aged 40 years or more, the mean ages in our cohorts of those cancers that also affect younger people are artefactually high. The proportion of cases that were male increased for all cancers over time except for lung and pancreatic. The proportion of patients with recorded symptoms for each of the cancers increased between 2001–2002 and 2007–2008.

Diagnostic intervals

First presentation of any cancer-related symptom

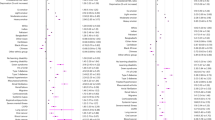

The diagnostic intervals in 2001–2002 and 2007–2008 for each cancer are summarised in Table 2. There was a reduction in mean diagnostic interval of 5.4 days (95% CI: 2.4–8.5; P<0.001) from 2001–2002 to 2007–2008 for first presentation of any cancer symptom. There was significant evidence at the 5% level of reductions for six cancers (mean reduction; 95% confidence interval): kidney (20.4 days; −0.5 to 41.5), head and neck (21.2 days; 0.2–41.6), bladder (16.4 days; 6.6–26.5), colorectal (9.0 days; 3.2–14.8), oesophageal (13.1 days; 3.0–24.1), and pancreatic (12.6 days; 0.2–24.6). Median diagnostic intervals were longer for all cancers, except leukaemia and myeloma, in Cohort 1 compared with Cohort 2. For the 2007–2008 cohort, the cancers with the shortest median diagnostic intervals were breast (26 days), testicular (44 days), and oesophageal (58 days); and those with the longest were myeloma (156 days), lung (112 days), and lymphoma (99 days). Similarly, the cancers with the shortest 90th centile diagnostic intervals were testicular (113 days), breast (203 days), and cervical (232 days); and those with the longest were myeloma (336 days), lung (325 days), and gastric (315 days). The 90th centile diagnostic intervals were 4–7 months for both cohorts for breast and testicular cancers and >9 months for both cohorts for all other cancers (except cervical Cohort 2).

Differences by NICE-qualifying symptom category

For most of the cancers, patients in both cohorts who presented with NICE-qualifying symptoms had shorter diagnostic intervals than those who did not (gastric, cervical, and kidney cancer in Cohort 1 being the exceptions). Tests of interaction provided little evidence of differences between the NICE categories with respect to change in mean diagnostic interval between the two cohorts, with the exception of oesophageal cancer (P-value for interaction test=0.03), where there was a 16.8-day reduction for the NICE-qualifying symptom group and a 39.4-day increase for the non-NICE symptom group, and cervical cancer (P-value for interaction test=0.006), where there was a 55.4-day reduction for the NICE-qualifying symptom group and a 22.0-day increase for the non-NICE symptom group (Table 3).

Discussion

For a group of 15 cancers, time from first presentation to the general practitioner to diagnosis reduced between 2001–2002 and 2007–2008. The size of the reduction differed across cancers. The values for the 90th centiles of the distributions remain very high for some cancers, and indeed increased for four cancer types. for the 2007–2008 cohort, median diagnostic intervals remained >2 months for 10 of the 15 cancers studied, while for 13 of the 15 cancers, 1 in 10 patients had a diagnostic interval of over 7 months. It is reasonable to suggest that these findings have clinical significance for some of the cancers. There were large differences in diagnostic intervals among cancer sites. There is now good evidence, using robust methods, for better survival in colorectal cancer with shorter diagnostic intervals (Tørring et al, 2011). This is likely to be true in other cancers also. Hence, our view is that even modest reductions in diagnostic intervals (such as shown in our paper for some, but not all, of the cancers studied), across large populations, are likely to make a difference in stage and survival to some patients. This is clearly accepted at policy level (for example, for NAEDI in England) and it is estimated that about half of the difference in survival is due to ‘late diagnosis’ (Abdel-Rahman et al, 2009). For the cancers where there was no or minimal change, an alternative explanation is that extensive efforts to improve diagnostic times over this time period were unsuccessful.

There are two bodies of evidence of relevance to this paper. These are previous studies of the duration of cancer diagnostic intervals, and the effects of interventions to reduce cancer diagnostic time. For the former we were aware of the paucity of evidence in this area, given the lack of past interest in the concept of the ‘diagnostic interval’. For the latter, there has been a recent systematic review that has addressed this topic (Mansell et al, 2011). This included 22 studies reporting interventions (predominantly educational) to reduce ‘primary care delay’, with a variety of outcomes. Although some of these did report positive effects, for example on diagnostic accuracy, none of the included papers reported any measures of timeliness or delay.

Direct comparisons of diagnostic intervals with previous studies and with other countries are difficult for two reasons: first because of differences in the measurement and definition of ‘diagnostic intervals’ (Weller et al, 2012), and second because of the dearth of the literature. We are aware of only one recent feasibility study that has reported diagnostic intervals per se (Murchie et al, 2012); this is because the diagnostic interval is a recent concept, but one that we think is important because it is modifiable and relatively easy to measure. Many other studies have reported other time intervals of the diagnostic journey but this is the first to report diagnostic intervals across different time periods on such a scale and in 15 cancers. A recent systematic review of interventions to reduce primary care delay reported no data on the duration of diagnostic intervals (Mansell et al, 2011).

Our results are in keeping with previous findings that suggest fast-track referrals may perversely lengthen waiting times for some patients routinely referred for suspected breast cancer (Potter et al, 2007) and may prioritise those with advanced disease in lung cancer, who are more likely to have ‘red flag’ symptoms (Allgar et al, 2006). For oesophageal and gastric cancers, our findings may reflect changes in clinical practice and reduced use of gastroscopy resulting from the 2005 NICE guidance on dyspepsia management (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2004). The 2005 Referral Guidelines for Suspected Cancer (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2005) were a major revision of the initial Department of Health guidelines in 2000 (Department of Health, 2000), and were implemented widely in primary and secondary care. It is entirely plausible that, augmented by service redesign – in particular 2-week clinics, some of which were established before 2005, but which were fully established by 2005 – they have contributed to the falling diagnostic intervals. While we cannot draw conclusions about causality, we suggest that change may have resulted, at least in part, from implementation of the 2005 NICE guidelines. It is likely that an increased awareness of symptoms and symptom clusters in primary care has led to earlier referral for specialist opinion or diagnostic investigation, although more streamlined diagnostic processes in secondary care may also have had an influence.

The main strength of this study is that it uses a large, longitudinal, high-quality, and validated UK general practice data set, that has previously been used for cancer diagnostic studies (Jones et al, 2007; Dommett et al, 2012); and recent systematic reviews have confirmed the validity of diagnostic coding within GPRD (Herrett et al, 2010; Khan et al, 2010). While there are potential methodological issues in measuring diagnostic intervals, a recent consensus statement (Weller et al, 2012) makes recommendations on the design of studies recording the first presentation of symptoms, the use of primary care databases being recommended. Our definitions and reporting are in keeping with these recommendations. Our findings regarding the numbers of patients with recorded symptoms are compatible with the proportion of patients diagnosed as emergency presentations (Elliss-Brookes et al, 2012). The study specifically relates to the diagnostic interval only – the time period when diagnostic activity takes place; hence it informs the development of interventions to reduce this.

There are a number of limitations to this study and the findings must be interpreted with some caution. First the study design does not permit us to infer causality, and only reports an association (although a very plausible one). A number of changes in policy and practice may have contributed to changes in diagnostic intervals over time, the implementation of the 2005 NICE Referral Guidelines for Suspected Cancer being only one of them. Secondly, this study was dependent upon coded symptoms, and it is inevitable that some symptoms were not recorded, or were recorded in an inaccessible field (so-called ‘free-text’). Recent GPRD studies, however, indicate that free-text data usually just confirms that which has been entered in a coded (and therefore accessible) form (Tate et al, 2011), and electronic records have been found to be similar to paper records (Hamilton et al, 2003). Furthermore, there will be some cancers that presented with symptoms that had not been included in our defined list; these patients would not have been included in our analysis and are likely to have different patterns of presentation. We have also assumed that the symptom identified in the record was caused by the cancer, when it may have been co-incidental. Although we were not able to specifically identify screen-detected patients, it is likely that they would have had no symptoms, and would therefore have been excluded. Third, we chose to apply a cut-off point for symptoms of 12 months prior to the date of diagnosis. Some diagnostic intervals may have been longer than this, although the likely effect is small. Had we prolonged the duration we would have captured both more patients with genuine diagnostic intervals of greater than 1 year, and more patients with symptoms that were unrelated to their subsequent cancer diagnosis. This is also an area where there may be variation between cancers; however, for consistency and because there are no methodological precedents we used the time period of 12 months for all of the cancers. Fourth, caution needs to be applied to the interpretation of data for some specific cancer sites or groups. For example, people under the age of 40 years were not included in the data sets. This was a practical decision because most cancers are rare below this age and, when they do occur, may be atypical, for example being part of a familial syndrome. Heterogeneity within certain cancer groups (leukaemia, head and neck), may also limit the generalisability of our findings. All of these issues, however, are mitigated by the fact that they would have affected both cohorts in similar, but not identical ways, since the numbers of patients and the numbers of symptoms in the cohorts vary. Last, GPRD did not (at the time of analysis) permit linkage with hospital data.

We have found that diagnostic intervals for cancer in England reduced between 2001–2002 and 2007–2008. We propose that the implementation of cancer referral guidelines may have had some influence. Within each cohort, the contrast between the diagnostic intervals for patients with and without non-NICE-qualifying symptoms is stark. The findings do not tell us, however, that NICE-qualifying symptoms are necessarily the right symptoms to prioritise. For example, we know that mild anaemia as a first symptom of colorectal cancer has a higher mortality than severe anaemia (Stapley et al, 2006), the implication being that ‘softer’ symptoms may go undetected for longer. Indeed a fast-track system may disadvantage patients who do not fulfil the criteria (Jones et al, 2001; Allgar et al, 2006). There is still a considerable challenge for policy and practice to further expedite diagnosis. The median diagnostic intervals vary considerably between cancers, and some remain very long. The 90th centile of the distribution remains very long in some cancers. These findings, when compared with data from studies of other measures of time intervals in the diagnostic process (Allgar and Neal, 2005; Hansen et al, 2011), show that delays in diagnosis happen at different stages in different cancers, hence interventions to expedite diagnosis need to be carefully tailored. Expediting diagnoses for ‘red flag’ symptoms may be relatively straightforward; expediting it for all symptoms remains a challenge. At present, a range of initiatives is being implemented in general practice in order to achieve this (Rubin et al, 2011). We have described a method of measuring the diagnostic interval and have provided a baseline against which these initiatives can be assessed.

References

Abdel-Rahman M, Stockton D, Rachet B, Hakulinen T, Coleman MP (2009) What if cancer survival in Britain were the same as in Europe: how many deaths are avoidable? Br J Cancer 101: S115–S124.

Allgar VL, Neal RD (2005) Delays in the diagnosis of six cancers: analysis of data from the National Survey of NHS Patients: Cancer. Br J Cancer 92: 1959–1970.

Allgar V, Neal RD, Ali N, Leese B, Heywood P, Proctor G, Evans J (2006) Urgent general practitioner referrals for suspected lung, colorectal, prostate and ovarian cancer. Br J Gen Pract 56: 355–362.

Corner J, Hopkinson J, Fitzsimmons D, Barclay S, Muers M (2005) Is late diagnosis of lung cancer inevitable? Interview study of patients' recollections of symptoms before diagnosis. Thorax 60: 314–319.

Davison AC, Hinkley DV (1997) Bootstrap Methods and their Application. Cambridge University Press: New York, USA.

Department of Health (2007) Cancer Reform Strategy. Department of Health: London.

Department of Health (2000) Referral Guidelines for Suspected Cancer. Department of Health: London.

Department of Health (1997) The New NHS: Modern, Dependable. Department of Health: London.

Department of Health (2011) Improving Outcomes: A Strategy For Cancer. Department of Health: London.

Dommett RM, Redaniel MT, Stevens MCG, Hamilton W, Martin RM (2012) Features of childhood cancer in primary care: a population-based nested case–control study. Br J Cancer 106: 982–987.

Elliss-Brookes L, McPhail S, Greenslade M, Shelton J, Hiom S, Richards M (2012) Routes to diagnosis for cancer – determining the patient journey using multiple routine data sets. Br J Cancer 107: 1220–1226.

Hamilton WT, Round AP, Sharp D, Peters TJ (2003) The quality of record keeping in primary care: a comparison of computerised, paper and hybrid systems. Br J Gen Pract 53: 929–933.

Hamilton W (2009) The CAPER studies: five case-control studies aimed at identifying and quantifying the risk of cancer in symptomatic primary care patients. Br J Cancer 101: S80–S86.

Hamilton W (2010) Cancer diagnosis in primary care. Br J Gen Pract 60: 121–128.

Hansen RP, Vedsted P, Sokolowski I, Sondergaard J, Olesen F (2011) Time intervals from first symptom to treatment of cancer. A cohort study of 2212 newly diagnosed cancers patients. BMC Health Services Res 11: 284.

Herrett E, Thomas SL, Schoonen WM, Smeeth L, Hall AJ (2010) Validation and validity of diagnoses in the General Practice Research Database: a systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol 69: 4–14.

Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C (2012) Identifying women with suspected ovarian cancer in primary care: derivation and validation of algorithm. BMJ 344: d8009.

Jones R, Rubin G, Hungin P (2001) Is the two week rule for cancer referrals working? BMJ 322: 1555–1556.

Jones R, Latinovic R, Charlton J, Gulliford MC (2007) Alarm symptoms in early diagnosis of cancer in primary care: cohort study using the General Practice Research Database. BMJ 334: 1040.

Khan NF, Harrison SE, Rose PW (2010) Validity of diagnostic coding within the General Practice Research Database: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract 60: e128–e136.

Leeds North West PCT (2005) Cancer Equity Audit. Leeds North West PCT pp 12-13. Available at: http://www.york.ac.uk/yhpho/documents/hea/Website/NW%20PCT%20Cancer%20Equity%20Audit_Copy.pdf (accessed on 10/12/2013).

Lyratzopoulos G, Neal RD, Barbiere JM, Rubin G, Abel G (2012) Variation in the number of general practitioner consultations before hospital referral for cancer: findings from a national patient experience survey. Lancet Oncol 13: 353–365.

Mansell G, Shapley M, Jordan JL, Jordan K (2011) Interventions to reduce primary care delay in cancer referral: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract 61: e821–e835.

Murchie P, Campbell NC, Delaney EK, Dinant G-J, Hannaford PC, Johansson L, Lee AJ, Rollano P, Spigt M (2012) Comparing diagnostic delay in cancer: a cross-sectional study in three European countries with primary care-led health care systems. Family Pract 29: 69–78.

National Cancer Information Network (2011) Urgent GP referral rates for suspected cancer. NCIN Data Briefing.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2004) Dyspepsia. Management of dyspepsia in adults in primary care: London.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2005) Referral Guidelines for Suspected Cancer. NICE: London.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2011) The recognition and initial management of ovarian cancer. NICE: London.

Neal RD (2009) Do diagnostic delays in cancer matter? Br J Cancer 101: S9–12.

Olesen F, Hansen RP, Vedsted P (2009) Delay in diagnosis: the experience in Denmark. Br J Cancer 101: S5–S8.

Potter S, Govindarajulu S, Shere M, Braddon F, Curran G, Greenwood R, Sahu AK, Cawthorn SJ (2007) Referral patterns, cancer diagnoses, and waiting times after introduction of two week wait rule for breast cancer: prospective cohort study. BMJ 335: 288–291.

Richards MA, Westcombe AM, Love SB, Littlejohns P, Ramirez AJ (1999) Influence of delay on survival of patients with breast cancer: systematic review. Lancet 353: 1119–1126.

Richards MA (2009) The National Awareness and Early Diagnosis Initiative in England: assembling the evidence. Br J Cancer 101: S1–S4.

Rubin GP, McPhail S, Elliott K (2011) National Audit of Cancer Diagnosis in Primary Care. Royal College of General Practitioners: London.

Rubin G, Vedsted P, Emery J (2011) Improving cancer outcomes: better access to diagnostics in primary care could be critical. Br J Gen Pract 61: 317–318.

Stapley S, Peters TJ, Sharp D, Hamilton W (2006) The mortality of colorectal cancer in relation to the initial symptom and to the duration of symptoms: a cohort study in primary care. Br J Cancer 95: 1321–1325.

Tate AR, Martin AGR, Ali A, Cassell JA (2011) Using free text information to explore how and when GPs code a diagnosis of ovarian cancer: an observational study using primary care records of patients with ovarian cancer. BMJ Open 1: e000025.

Thompson SG, Barber JA (2000) How should costs data in pragmatic trials be analysed? BMJ 320: 1197–1200.

Tørring ML, Frydenberg M, Hansen RP, Olesen F, Hamilton W, Vedsted P (2011) Time to diagnosis and mortality in colorectal cancer: a cohort study in primary care. Br J Cancer 104: 934–940.

Weller D, Vedsted P, Rubin G, Walter F, Emery J, Scott S, Campbell C, Andersen RS, Hamilton W, Olesen F, Rose P, Nafees S, van Rijswijk E, Muth C, Beyer M, Neal RD (2012) The Aarhus Statement: improving design and reporting of studies on early cancer diagnosis. Br J Cancer 106: 1262–1267.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the National Cancer Action Team and the Department of Health Cancer Policy Team. The views contained in it are those of the authors and do not represent Department of Health policy. We can confirm that the corresponding author has had full access to the data and final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. We would like to thank Rosemary Tate for early input into the protocol, staff of the GPRD for help in understanding the data. OCU is supported by the Peninsula Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care. Ethical approval: Independent Scientific Advisory Committee, numbers 09_0110 and 09_0111.

Author Contributions

The study was designed by RDN, GR and WH. NUD conducted the analysis with input from BC and OCU. SS helped in the preparation of the data set for analysis. RDN wrote the first draft of the paper. All authors commented on the manuscript. RDN will act as guarantor.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1

List of cancer specific symptoms, by cancer; and process of applying Read codes to cancer site specific and non-specific symptoms

The process of applying Read codes to cancer site specific and non-specific symptoms was developed using the Medical Dictionary Version 1.3.0 provided by GPRD. Different combinations of Read terms using both free text or specific medical term and wild card truncation, were used to maximise the scope of terms, and a list of possible terms prepared. The list was screened independently by GR, WH, and RDN and agreed. Symptom codes that had specific non-cancer causes mentioned in the code description were excluded unless they had a question mark. For example, ‘A083.11—Diarrhoea & vomiting -? Infect’ was included, whereas ‘A082.11—Travellers' diarrhoea’ was excluded. These lists were then used to identify the symptom codes for the period of 1 year prior to diagnosis (the lists are available from the authors on request). Two researchers (ND, SS) independently applied this process of identifying the symptom codes from the data set for a pilot cancer site (pancreatic) to compare and cross-validate the process of capturing the symptom codes. There was an 80.2% agreement between the two (Kappa statistics: score 0.62, 95% CI 0.51–0.73, P<0.001). The disagreement was on codes that were very vague/broad and almost invariably had very few occurrences. We have considerable experience in creating libraries of codes for symptoms, particularly in the field of cancer.

Appendix 2

NICE qualifying symptoms and assumptions made in their classification

A number of assumptions had to be made in this process. These were as follows:

-

Symptoms with a qualifying symptom duration. For example, several symptoms qualify if they are ‘persistent’ or present for a specific number of weeks. In these circumstances, we had to make the assumption that the symptom always fulfilled the duration.

-

Symptoms with a qualifying age. For example, dyspepsia for upper gastrointestinal cancers in patients aged over 55. In these circumstances we applied this age criterion to the data set.

-

Symptoms with a qualifying description. For example, breast lumps are qualifying if they are, ‘hard’, ‘tethered’, or ‘present after next period’. They are, however, rarely coded in such detail, hence we included ‘breast lump’ (and its synonyms) as a qualifying symptom, without further description.

-

Symptoms needing qualification by another. There were two instances of this. ‘Unexplained upper abdominal pain with weight loss’ for pancreatic cancer, and ‘Persistent urinary tract infections with haematuria’. We agreed that abdominal pain and urinary tract infections, alone, would be qualifying symptoms for their respective cancers.

-

Implicit qualifying symptom. ‘Anaemia’ is not strictly listed as a qualifying symptom for haematological cancers, even though there is much reference to it in the guideline. We agreed that it should be classified as such.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Neal, R., Din, N., Hamilton, W. et al. Comparison of cancer diagnostic intervals before and after implementation of NICE guidelines: analysis of data from the UK General Practice Research Database. Br J Cancer 110, 584–592 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2013.791

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2013.791

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Adopting standardized cancer patient pathways as a policy at different organizational levels in the Swedish Health System

Health Research Policy and Systems (2023)

-

Priorities for implementation research on diagnosing cancer in primary care: a consensus process

BMC Health Services Research (2023)

-

A taxonomy of early diagnosis research to guide study design and funding prioritisation

British Journal of Cancer (2023)

-

Merging existing practices with new ones: the adjustment of organizational routines to using cancer patient pathways in primary healthcare

BMC Health Services Research (2022)

-

Equitable access to cancer patient pathways in Norway – a national registry-based study

BMC Health Services Research (2021)