-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

L H Rasmussen, M Lawaetz, L Bjoern, B Vennits, A Blemings, B Eklof, Randomized clinical trial comparing endovenous laser ablation, radiofrequency ablation, foam sclerotherapy and surgical stripping for great saphenous varicose veins, British Journal of Surgery, Volume 98, Issue 8, August 2011, Pages 1079–1087, https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.7555

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

This randomized trial compared four treatments for varicose great saphenous veins (GSVs).

Five hundred consecutive patients (580 legs) with GSV reflux were randomized to endovenous laser ablation (980 and 1470 nm, bare fibre), radiofrequency ablation, ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy or surgical stripping using tumescent local anaesthesia with light sedation. Miniphlebectomies were also performed. The patients were examined with duplex imaging before surgery, and after 3 days, 1 month and 1 year.

At 1 year, seven (5·8 per cent), six (4·8 per cent), 20 (16·3 per cent) and four (4·8 per cent) of the GSVs were patent and refluxing in the laser, radiofrequency, foam and stripping groups respectively (P < 0·001). One patient developed a pulmonary embolus after foam sclerotherapy and one a deep vein thrombosis after surgical stripping. No other major complications were recorded. The mean(s.d.) postintervention pain scores (scale 0–10) were 2·58(2·41), 1·21(1·72), 1·60(2·04) and 2·25(2·23) respectively (P < 0·001). The median (range) time to return to normal function was 2 (0–25), 1 (0–30), 1 (0–30) and 4 (0–30) days respectively (P < 0·001). The time off work, corrected for weekends, was 3·6 (0–46), 2·9 (0–14), 2·9 (0–33) and 4·3 (0–42) days respectively (P < 0·001). Disease-specific quality-of-life and Short Form 36 (SF-36®) scores had improved in all groups by 1-year follow-up. In the SF-36® domains bodily pain and physical functioning, the radiofrequency and foam groups performed better in the short term than the others.

All treatments were efficacious. The technical failure rate was highest after foam sclerotherapy, but both radiofrequency ablation and foam were associated with a faster recovery and less postoperative pain than endovenous laser ablation and stripping.

Introduction

Varicose veins are common and affect approximately 25 per cent of Western adults1. The condition is most often associated with great saphenous vein (GSV) reflux. Until recently, standard treatment has been surgery, with high ligation and stripping to knee level, combined with phlebectomies. Such treatment efficiently reduces symptoms, improves quality of life (QoL), and reduces the rate of reoperation compared with high ligation and phlebectomies only2–4. However, the operation may occasionally be associated with significant postoperative morbidity, including bleeding, groin infection, thrombophlebitis and saphenous nerve damage. Major complications are rare5. Conventional surgery is most often performed in hospital and using general or regional anaesthesia, which may increase costs.

In the past decade, alternative treatments such as endovenous ablation of the GSV with laser (EVLA), radiofrequency ablation (RFA) and ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy (UGFS) have gained popularity. Performed as office-based procedures using tumescent local anaesthesia, the new minimally invasive techniques have been shown in numerous studies to eliminate the GSV from the circulation safely and effectively6–9. A few randomized trials have compared the endovascular methods with conventional surgery. The first-generation RFA device, VNUS Closure™ (VNUS Medical Technologies, San Jose, California, USA), had comparable efficacy to surgery, but was associated with an earlier return to normal activity and improved QoL in the short term. The randomized trials of EVLA have shown efficacy comparable to surgery, but conflicting results concerning recovery10–13. Recently, an improved version of the first generation of RFA device, called ClosureFAST™ (VNUS Medical Technologies), was introduced9. There are only two randomized trials comparing UGFS with surgery; they showed no difference in short-term efficacy but less postoperative pain and earlier return to normal activities in patients treated with UGFS8,14,15.

The new minimally invasive methods have not previously been compared with each other and conventional surgery in the same randomized trial. The aim of this randomized trial was to compare EVLA, RFA (ClosureFAST™), UGFS and surgical stripping in patients with varicose veins and GSV insufficiency.

Methods

The regional ethics committee approved the study, which was designed as a consecutive randomized trial, and conducted in two private surgical centres that work under contract to the national healthcare system in Denmark. Every treatment procedure was performed by one of three experienced surgeons who had performed more than 100 EVLA procedures, 100 UGFS treatments, 25 ClosureFAST™ procedures and more than 1000 stripping procedures before the start of the study. RFA was performed in only one centre (Naestved). Consecutive patients referred for varicose vein treatment by the family physician were randomized in the two sites in blocks of 12 sealed envelopes to one of the four treatments. In addition to treatment of the GSV, miniphlebectomies were performed with the intention of removing all varicosities during the same procedure.

Inclusion criteria were: age 18–75 years; symptomatic varicose veins; Clinical Etiologic Anatomic Pathophysiologic (CEAP) class C2–4EpAsPr; GSV incompetence, defined by a reflux time of more than 0·5 s on duplex imaging (Hawk 7–10-MHz probe; BK Medical, Herlev, Denmark)16; and informed consent provided. The patients were examined in the standing position, and reflux was measured after manual compression and release of the calf. Bilateral treatment was permitted, provided that both legs had the same treatment during the same operation. Patients with recurrent varicose veins were also included if the GSV was preserved to the groin on duplex imaging.

Exclusion criteria were: duplication of the saphenous trunk or an incompetent anterior accessory saphenous vein; small saphenous vein reflux (until 3 months after removal of such a vein); previous deep vein thrombosis (DVT); history of arterial insufficiency or ankle : brachial pressure index below 0·9, or both; axial deep venous insufficiency (femoral or popliteal vein, or both); and tortuous GSV rendering the vein unsuitable for endovenous treatment.

Treatment

All treatments were performed in a treatment room under tumescent local anaesthesia, using a solution of 0·1 per cent lidocaine with adrenaline and bicarbonate. The solution was administered using an infusion pump (Nouvag, Goldach, Switzerland) under ultrasound guidance. In the UGFS group, only the varicosities were anaesthetized. The aim was to administer 10 ml per cm GSV tumescent anaesthesia in the other groups. A light sedative and analgesic (midazolam and alfentanil or diazepam) were administered intravenously before the procedure in most patients.

The surgical procedure was carried out through a 4–6-cm incision in the groin, with flush ligation of the GSV and division of all tributaries to the second level of division. The GSV was then removed using a pin-stripper to just below the knee.

The EVLA procedure was performed under duplex guidance with a 980-nm diode laser (Ceralas D 980; Biolitec, Jena, Germany) for the first 17 patients and a 1470-nm diode laser (Ceralas D 1470) for the rest. A bare-tip fibre was used for all EVLA treatments. In one centre (Roskilde) the pulse mode was used (20 patients), whereas continuous mode was used in Naestved. For thermoablation, the GSV was cannulated just below the knee or at the lowest point of reflux on the thigh. The laser fibre was advanced until 2 cm below the saphenofemoral junction, after which the GSV was ablated during withdrawal of the fibre.

The RFA procedure was performed according to the manufacturer's recommendations as described elsewhere9. In brief, the treatment consisted of segmental heating of the GSV, using a catheter with a 7-cm heating element (VNUS Medical Technologies). The catheter was advanced under ultrasound guidance to 2 cm below the saphenofemoral junction before the start of ablation. The temperature was maintained at 120° for 20 s per segment using a thermocouple on the heating element, which provided a feedback loop to the generator during withdrawal.

The UGFS treatment was performed with the patient in the reversed Trendelenburg position. A 5-Fr cannula was inserted in the GSV just above the knee under ultrasound guidance. The foam consisted of a 3 per cent solution of polidocanol (Aethoxysclerol®; Kreussler, Wiesbaden, Germany); 2 ml solution mixed with 8 ml air was prepared according to the method of Tessari8. Before injection, the table was tilted to the Trendelenburg position. The injection of foam was monitored using ultrasound, and continued until the foam reached the saphenofemoral junction, and the GSV was seen to contract for its entire length in the thigh.

As the last step of the treatment, all varicose veins were removed by phlebectomy in all groups. Retreatment with foam was allowed within 1 month in the UGFS group.

After the procedure, the leg was wrapped in sterile absorbent bandages and covered with a cohesive compression bandage for 48 h. In the UGFS group the patients were then instructed to use a 30-mmHg compression stocking to the groin, whereas the other patients used a short 20-mmHg stocking, for 2 weeks. No specific analgesia was prescribed. All patients were encouraged to resume work and normal activity as soon as they were able.

Assessments

The patients were examined at the time of randomization, and after 3 days, 1 month and 1 year. It is intended to continue follow-up yearly for 5 years after the treatment. At the initial visit, the surgeon obtained the medical history, performed a clinical and duplex examination, and determined the CEAP class and Venous Clinical Severity Score (VCSS)17,18. The duration of reflux and the diameter of the GSV 3 cm below the saphenofemoral junction were measured. The Aberdeen Varicose Vein Symptom Severity Score (AVVSS) and the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36 (SF-36®; QualityMetric, Lincoln, Rhode Island, USA) health-related QoL score were completed by the patients and recorded. The AVVSS is a validated instrument for measurement of disease-specific QoL in patients with varicose veins. It produces a score from 0 (no venous symptoms) to 100 (worst venous symptoms)19. The SF-36® is a generic QoL instrument, which consists of eight domains: physical functioning, role—physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role—emotional and mental health. Each domain is scored form 0 (worst) to 100 (best)20.

At all subsequent visits, the patients were examined clinically and with duplex imaging by the surgeon. They were asked to indicate the exact date of return to work and normal activity. The technical result and complications were recorded, and patients completed the AVVSS and the SF-36®. The patients also registered a pain score on a visual analogue scale from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst imaginable pain) for the first 10 days after treatment21. The research nurse recorded the pain score, AVVSS and SF-36® responses, and a statistician calculated the scores.

Criteria for technical success were closed or absent GSV with lack of flow. A recanalized GSV or treatment failure was defined as an open part of the treated vein segment more than 10 cm in length. Complications were regarded as minor if they required no therapy, and major if they required treatment, admission to hospital, or led to permanent adverse sequelae or death.

Calculation of costs was based on the standard reimbursement for high ligation and stripping, with the addition of the costs of equipment for thermoablation and the standard salary and productivity level in Denmark. The impact of sick leave on costs was corrected for weekends.

Statistical analysis

The primary endpoint for the study was GSV closure, and secondary endpoints were pain, absence from work and normal activity, scores for SF-36®, AVVSS and VCSS, and recurrence rates. A priori sample size calculations indicated that, to detect a 15 per cent difference in closed or absent GSVs between the groups with α = 5 and β = 80, 60 legs would be needed in each group. With respect to pain score and the bodily pain domain in SF-36®, 46 patients in each group would be necessary to describe a significant difference of 20 per cent.

Efficacy and safety were assessed for the full analysis set, comprising all patients undergoing treatment. Descriptive summary statistics were used for safety analysis. The primary endpoint was analysed using logistic regression. ANCOVA models with repeated measurements were used for analysis of efficacy endpoints, AVVSS, SF-36®scores and pain scores. The time from treatment to resumption of work or normal activity was analysed using log rank statistics. The Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare VCSS values. Significance was set at the 5 per cent level. The analyses were performed in SAS® version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

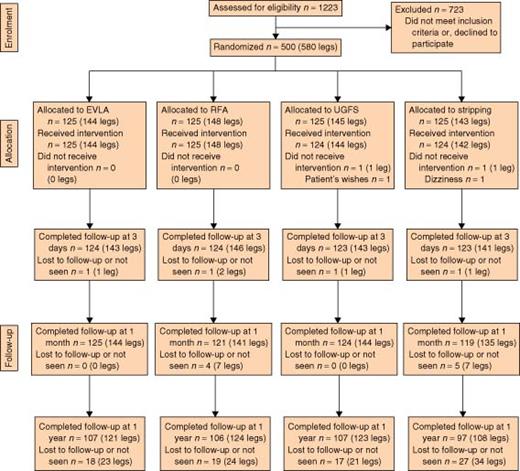

Between February 2007 and July 2009, 500 consecutive patients (580 legs) were randomized to receive treatment (Fig. 1) There was no difference between the groups regarding the numbers lost or length of follow-up. The four groups were well matched for demographic data, CEAP class and GSV details (Table 1). The energy deposition in the EVLA group and volume of foam used per leg is also shown in Table 1.

CONSORT diagram for the trial. EVLA, endovenous laser ablation; RFA, radiofrequency ablation; UGFS, ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy

Demographic data and treatment characteristics for patients with varicose veins and great saphenous vein incompetence

| . | EVLA . | RFA . | UGFS . | Stripping . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 125 | 125 | 124 | 124 |

| No. of legs | 144 | 148 | 144 | 142 |

| Bilateral veins | 19 | 23 | 20 | 18 |

| Age (years)* | 52 (18–74) | 51 (23–75) | 51 (18–75) | 50 (19–72) |

| Women (%) | 72 | 70 | 76 | 77 |

| CEAP C2–C3 (legs) | 95 | 92 | 96 | 97 |

| CEAP C4–C6 (legs) | 5 | 8 | 4 | 3 |

| Previous surgery | 9 | 7 | 4 | 8 |

| GSV diameter (mm)* | 7·6 (3–12) | 7·2 (3–12) | 8·7 (3–20) | 7·8 (3–14) |

| Length of treated GSV (cm)* | 35 (14–49) | 34 (13–51) | — | — |

| Energy (J/cm)* | 76·5 (43–128) | — | — | — |

| Volume of foam (ml)* | — | — | 8 (4–15) | — |

| No. of phlebectomies* | 14 (1–43) | 16 (10–80) | 15 (1–43) | 15 (1–48) |

| Tumescence (ml)* | 293 (50–650) | 335 (32–690) | 8·5 (4–100) | 316 (50–900) |

| Surgeon's time (min)* | 26 (12–80) | 27 (12–80) | 19 (5–145) | 32 (15–80) |

| . | EVLA . | RFA . | UGFS . | Stripping . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 125 | 125 | 124 | 124 |

| No. of legs | 144 | 148 | 144 | 142 |

| Bilateral veins | 19 | 23 | 20 | 18 |

| Age (years)* | 52 (18–74) | 51 (23–75) | 51 (18–75) | 50 (19–72) |

| Women (%) | 72 | 70 | 76 | 77 |

| CEAP C2–C3 (legs) | 95 | 92 | 96 | 97 |

| CEAP C4–C6 (legs) | 5 | 8 | 4 | 3 |

| Previous surgery | 9 | 7 | 4 | 8 |

| GSV diameter (mm)* | 7·6 (3–12) | 7·2 (3–12) | 8·7 (3–20) | 7·8 (3–14) |

| Length of treated GSV (cm)* | 35 (14–49) | 34 (13–51) | — | — |

| Energy (J/cm)* | 76·5 (43–128) | — | — | — |

| Volume of foam (ml)* | — | — | 8 (4–15) | — |

| No. of phlebectomies* | 14 (1–43) | 16 (10–80) | 15 (1–43) | 15 (1–48) |

| Tumescence (ml)* | 293 (50–650) | 335 (32–690) | 8·5 (4–100) | 316 (50–900) |

| Surgeon's time (min)* | 26 (12–80) | 27 (12–80) | 19 (5–145) | 32 (15–80) |

Values are mean (range). EVLA, endovenous laser ablation; RFA, radiofrequency ablation; UGFS, ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy; CEAP, Clinical Etiologic Anatomic Pathophysiologic; GSV, great saphenous vein.

Demographic data and treatment characteristics for patients with varicose veins and great saphenous vein incompetence

| . | EVLA . | RFA . | UGFS . | Stripping . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 125 | 125 | 124 | 124 |

| No. of legs | 144 | 148 | 144 | 142 |

| Bilateral veins | 19 | 23 | 20 | 18 |

| Age (years)* | 52 (18–74) | 51 (23–75) | 51 (18–75) | 50 (19–72) |

| Women (%) | 72 | 70 | 76 | 77 |

| CEAP C2–C3 (legs) | 95 | 92 | 96 | 97 |

| CEAP C4–C6 (legs) | 5 | 8 | 4 | 3 |

| Previous surgery | 9 | 7 | 4 | 8 |

| GSV diameter (mm)* | 7·6 (3–12) | 7·2 (3–12) | 8·7 (3–20) | 7·8 (3–14) |

| Length of treated GSV (cm)* | 35 (14–49) | 34 (13–51) | — | — |

| Energy (J/cm)* | 76·5 (43–128) | — | — | — |

| Volume of foam (ml)* | — | — | 8 (4–15) | — |

| No. of phlebectomies* | 14 (1–43) | 16 (10–80) | 15 (1–43) | 15 (1–48) |

| Tumescence (ml)* | 293 (50–650) | 335 (32–690) | 8·5 (4–100) | 316 (50–900) |

| Surgeon's time (min)* | 26 (12–80) | 27 (12–80) | 19 (5–145) | 32 (15–80) |

| . | EVLA . | RFA . | UGFS . | Stripping . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 125 | 125 | 124 | 124 |

| No. of legs | 144 | 148 | 144 | 142 |

| Bilateral veins | 19 | 23 | 20 | 18 |

| Age (years)* | 52 (18–74) | 51 (23–75) | 51 (18–75) | 50 (19–72) |

| Women (%) | 72 | 70 | 76 | 77 |

| CEAP C2–C3 (legs) | 95 | 92 | 96 | 97 |

| CEAP C4–C6 (legs) | 5 | 8 | 4 | 3 |

| Previous surgery | 9 | 7 | 4 | 8 |

| GSV diameter (mm)* | 7·6 (3–12) | 7·2 (3–12) | 8·7 (3–20) | 7·8 (3–14) |

| Length of treated GSV (cm)* | 35 (14–49) | 34 (13–51) | — | — |

| Energy (J/cm)* | 76·5 (43–128) | — | — | — |

| Volume of foam (ml)* | — | — | 8 (4–15) | — |

| No. of phlebectomies* | 14 (1–43) | 16 (10–80) | 15 (1–43) | 15 (1–48) |

| Tumescence (ml)* | 293 (50–650) | 335 (32–690) | 8·5 (4–100) | 316 (50–900) |

| Surgeon's time (min)* | 26 (12–80) | 27 (12–80) | 19 (5–145) | 32 (15–80) |

Values are mean (range). EVLA, endovenous laser ablation; RFA, radiofrequency ablation; UGFS, ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy; CEAP, Clinical Etiologic Anatomic Pathophysiologic; GSV, great saphenous vein.

Primary outcome measure: failure rates

The number of GSVs that were patent or not stripped successfully at follow-up is shown in Table 2. Significantly more GSVs were open and refluxing at 1 year in the UGFS group than in the other groups (P < 0·001). There was no statistically significant difference in patent GSVs in the three other groups (P = 0·543). Four stripping procedures failed because the veins broke and could not be retrieved from below the knee. All recanalized GSVs had flow and were refluxing, except one in the EVLA group, which was open at 1 year, contracted but not refluxing. The five GSVs that were open in the foam group during the first month were re-treated with foam sclerotherapy. After the first month, no further sclerotherapy was allowed. Fourteen (11·6 per cent), nine (7·3 per cent), 17 (13·8 per cent) and 16 (14·8 per cent) legs had recurrent varicose veins at 1-year follow-up in the EVLA, RFA, UGFS and stripping group respectively (P = 0·155).

Failure rates up to 1 year after treatment of varicose veins

| . | EVLA . | RFA . | UGFS . | Stripping . | P* . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 days | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (2·1) | 4 (2·8) | 0·053 |

| 1 month | 1 (0·7) | 0 (0) | 2 (1·4) | 3 (2·2) | 0·202 |

| 1 year | 7 (5·8) | 6 (4·8) | 20 (16·3) | 4 (4·8) | < 0·001 |

| . | EVLA . | RFA . | UGFS . | Stripping . | P* . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 days | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (2·1) | 4 (2·8) | 0·053 |

| 1 month | 1 (0·7) | 0 (0) | 2 (1·4) | 3 (2·2) | 0·202 |

| 1 year | 7 (5·8) | 6 (4·8) | 20 (16·3) | 4 (4·8) | < 0·001 |

Values in parentheses are percentage of legs. Failure was defined as a patent great saphenous vein (GSV) with reflux, or GSV not stripped successfully. EVLA, endovenous laser ablation; RFA, radiofrequency ablation; UGFS, ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy.

χ2 test.

Failure rates up to 1 year after treatment of varicose veins

| . | EVLA . | RFA . | UGFS . | Stripping . | P* . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 days | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (2·1) | 4 (2·8) | 0·053 |

| 1 month | 1 (0·7) | 0 (0) | 2 (1·4) | 3 (2·2) | 0·202 |

| 1 year | 7 (5·8) | 6 (4·8) | 20 (16·3) | 4 (4·8) | < 0·001 |

| . | EVLA . | RFA . | UGFS . | Stripping . | P* . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 days | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (2·1) | 4 (2·8) | 0·053 |

| 1 month | 1 (0·7) | 0 (0) | 2 (1·4) | 3 (2·2) | 0·202 |

| 1 year | 7 (5·8) | 6 (4·8) | 20 (16·3) | 4 (4·8) | < 0·001 |

Values in parentheses are percentage of legs. Failure was defined as a patent great saphenous vein (GSV) with reflux, or GSV not stripped successfully. EVLA, endovenous laser ablation; RFA, radiofrequency ablation; UGFS, ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy.

χ2 test.

Complications

Complications were mostly minor (Table 3). Only two events were classified as major complications. One patient had an iliac vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolus within 1 week of UGFS. The patient was subsequently treated with catheter-directed thrombolysis. The other had thrombosis of the popliteal vein within the first month after stripping. Significantly more patients in the RFA and foam groups developed postintervention superficial phlebitis. It was not recorded specifically whether the phlebitis was related to the GSV or the tributaries.

Complications in the first month after treatment of varicose veins

| . | EVLA . | RFA . | UGFS . | Stripping . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major | ||||

| Deep vein thrombosis | 0 | 0 | 1* | 1 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 0 | 0 | 1* | 0 |

| Minor | ||||

| Phlebitis | 4 | 12 | 17 | 5 |

| Infection | 0 | 1 | 4 | 1 |

| Paraesthesia | 3 | 6 | 2 | 5 |

| Hyperpigmentation | 3 | 8 | 8 | 6 |

| Haemorrhage | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| . | EVLA . | RFA . | UGFS . | Stripping . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major | ||||

| Deep vein thrombosis | 0 | 0 | 1* | 1 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 0 | 0 | 1* | 0 |

| Minor | ||||

| Phlebitis | 4 | 12 | 17 | 5 |

| Infection | 0 | 1 | 4 | 1 |

| Paraesthesia | 3 | 6 | 2 | 5 |

| Hyperpigmentation | 3 | 8 | 8 | 6 |

| Haemorrhage | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

Same patient. EVLA, endovenous laser ablation; RFA, radiofrequency ablation; UGFS, ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy. There was a significant difference in the incidence of phlebitis (P = 0·006, Fisher's exact test).

Complications in the first month after treatment of varicose veins

| . | EVLA . | RFA . | UGFS . | Stripping . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major | ||||

| Deep vein thrombosis | 0 | 0 | 1* | 1 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 0 | 0 | 1* | 0 |

| Minor | ||||

| Phlebitis | 4 | 12 | 17 | 5 |

| Infection | 0 | 1 | 4 | 1 |

| Paraesthesia | 3 | 6 | 2 | 5 |

| Hyperpigmentation | 3 | 8 | 8 | 6 |

| Haemorrhage | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| . | EVLA . | RFA . | UGFS . | Stripping . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major | ||||

| Deep vein thrombosis | 0 | 0 | 1* | 1 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 0 | 0 | 1* | 0 |

| Minor | ||||

| Phlebitis | 4 | 12 | 17 | 5 |

| Infection | 0 | 1 | 4 | 1 |

| Paraesthesia | 3 | 6 | 2 | 5 |

| Hyperpigmentation | 3 | 8 | 8 | 6 |

| Haemorrhage | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

Same patient. EVLA, endovenous laser ablation; RFA, radiofrequency ablation; UGFS, ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy. There was a significant difference in the incidence of phlebitis (P = 0·006, Fisher's exact test).

Secondary outcome measures

Pain scores

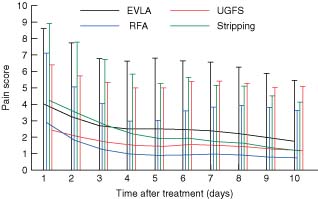

The sequence of pain scores during the first 10 days after the procedure is shown in Fig. 2. Patients in the RFA and UGFS groups reported significantly less postoperative pain than those in the EVLA and stripping groups (P < 0·001). Mean(s.d.) pain scores during the first 10 days were 2·58(2·41), 1·21(1·72), 1·60(2·04) and 2·25(2·23) in the EVLA, RFA, UGFS and stripping groups respectively. There was no statistically significant difference between EVLA and stripping or between RFA and UGFS. The number of phlebectomies did not significantly influence the pain scores (P = 0·136). Among patients who had EVLA, there was no significant difference in pain scores between treatments with the two different laser wavelengths.

Mean(s.d.) pain scores on a visual analogue scale from 0 to 10 for the first 10 days after treatment of varicose veins with endovenous laser ablation (EVLA), radiofrequency ablation (RFA), ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy (UGFS) and surgical stripping. P = 0·012 (ANOVA)

Return to normal activities and work

The time to resumption of normal activities and work was shorter in the groups treated with RFA and UGFS than in the EVLA and stripping groups (P < 0·001 for both RFA and UGFS) (Table 4). There was no statistically significant difference between laser treatment and surgery concerning return to normal activities and work (P = 0·184 and P = 0·258 respectively).

Time to resume normal activities and work, and cost of treatments

| . | EVLA . | RFA . | UGFS . | Stripping . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time to resume normal activity (days)* | 2 (0–25) | 1 (0–30) | 1 (0–30) | 4 (0–30) |

| Time to resume work (days)* | 3·6 (0–46) | 2·9 (0–14) | 2·9 (0–33) | 4·3 (0–42) |

| Procedure-related | ||||

| costs (€) | ||||

| Pretreatment | 189 | 189 | 189 | 189 |

| examination | ||||

| Reimbursement | 644 | 644 | 644 | 729 |

| Laser equipment | 366 | — | — | — |

| Radiofrequency | — | 442 | — | — |

| equipment | ||||

| Control duplex | 161 | 161 | 161 | 161 |

| imaging | ||||

| Total | 1360 | 1436 | 994 | 1079 |

| Indirect costs (€) | ||||

| Lost work | 840 | 560 | 560 | 1120 |

| Total costs (€) | 2200 | 1996 | 1554 | 2199 |

| . | EVLA . | RFA . | UGFS . | Stripping . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time to resume normal activity (days)* | 2 (0–25) | 1 (0–30) | 1 (0–30) | 4 (0–30) |

| Time to resume work (days)* | 3·6 (0–46) | 2·9 (0–14) | 2·9 (0–33) | 4·3 (0–42) |

| Procedure-related | ||||

| costs (€) | ||||

| Pretreatment | 189 | 189 | 189 | 189 |

| examination | ||||

| Reimbursement | 644 | 644 | 644 | 729 |

| Laser equipment | 366 | — | — | — |

| Radiofrequency | — | 442 | — | — |

| equipment | ||||

| Control duplex | 161 | 161 | 161 | 161 |

| imaging | ||||

| Total | 1360 | 1436 | 994 | 1079 |

| Indirect costs (€) | ||||

| Lost work | 840 | 560 | 560 | 1120 |

| Total costs (€) | 2200 | 1996 | 1554 | 2199 |

Values are median (range). Time to return to work was corrected for weekends. EVLA, endovenous laser ablation; RFA, radiofrequency ablation; UGFS, ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy.

Time to resume normal activities and work, and cost of treatments

| . | EVLA . | RFA . | UGFS . | Stripping . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time to resume normal activity (days)* | 2 (0–25) | 1 (0–30) | 1 (0–30) | 4 (0–30) |

| Time to resume work (days)* | 3·6 (0–46) | 2·9 (0–14) | 2·9 (0–33) | 4·3 (0–42) |

| Procedure-related | ||||

| costs (€) | ||||

| Pretreatment | 189 | 189 | 189 | 189 |

| examination | ||||

| Reimbursement | 644 | 644 | 644 | 729 |

| Laser equipment | 366 | — | — | — |

| Radiofrequency | — | 442 | — | — |

| equipment | ||||

| Control duplex | 161 | 161 | 161 | 161 |

| imaging | ||||

| Total | 1360 | 1436 | 994 | 1079 |

| Indirect costs (€) | ||||

| Lost work | 840 | 560 | 560 | 1120 |

| Total costs (€) | 2200 | 1996 | 1554 | 2199 |

| . | EVLA . | RFA . | UGFS . | Stripping . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time to resume normal activity (days)* | 2 (0–25) | 1 (0–30) | 1 (0–30) | 4 (0–30) |

| Time to resume work (days)* | 3·6 (0–46) | 2·9 (0–14) | 2·9 (0–33) | 4·3 (0–42) |

| Procedure-related | ||||

| costs (€) | ||||

| Pretreatment | 189 | 189 | 189 | 189 |

| examination | ||||

| Reimbursement | 644 | 644 | 644 | 729 |

| Laser equipment | 366 | — | — | — |

| Radiofrequency | — | 442 | — | — |

| equipment | ||||

| Control duplex | 161 | 161 | 161 | 161 |

| imaging | ||||

| Total | 1360 | 1436 | 994 | 1079 |

| Indirect costs (€) | ||||

| Lost work | 840 | 560 | 560 | 1120 |

| Total costs (€) | 2200 | 1996 | 1554 | 2199 |

Values are median (range). Time to return to work was corrected for weekends. EVLA, endovenous laser ablation; RFA, radiofrequency ablation; UGFS, ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy.

Venous Clinical Severity Score

The mean scores improved significantly after the procedure in all groups, with no significant difference between them (P < 0·001). Although the score improved in the majority of patients, one, one, seven and two patients had a worse score after EVLA, RFA, UGFS and stripping respectively.

Aberdeen Varicose Vein Symptom Severity Score

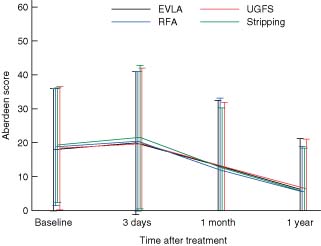

The score improved significantly in all groups from 1 month after surgery, with no difference between groups at any time (Fig. 3).

Mean(s.d.) disease-specific quality-of-life score (AVVSS) up to 1 year after treatment of varicose veins with endovenous laser ablation (EVLA), radiofrequency ablation (RFA), ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy (UGFS) and surgical stripping

Short Form 36 results

For all the groups and in all domains, there was a statistically significant improvement in most scores from pretreatment to 1 year (Table S1, supporting information). At 3 days, a clear reduction in scores was seen in all groups but, for the domains bodily pain, physical functioning and role—physical, patients treated with radiofrequency and foam had significantly better scores than the other two groups, indicating that patients in the stripping and EVLA groups had more pain and discomfort at 3 days. At 1 month, the difference between groups had disappeared.

Costs

A comparison of costs is shown in Table 4. The calculations were based on the reimbursement and productivity level in Denmark. Procedure-related costs were highest in the RFA group because of the higher cost of the catheter, and lowest in the UGFS group. When the cost of lost work was included in the total costs, UGFS was the cheapest, whereas EVLA and stripping were the most expensive procedures.

Discussion

Minimally invasive methods for ablation of the GSV have gained increasing popularity in the treatment of varicose veins. In the USA and elsewhere the endovenous techniques have more or less replaced conventional surgery. Although no longer-term randomized trials comparing the different methods with conventional surgery have been published, EVLA, RFA and UGFS have previously been compared with each other or with conventional surgery in randomized trials with short- and medium-term follow-up. Until now, no single trial has studied all methods together, and only two short-term studies have compared the ClosureFAST™ device with EVLA22,23.

The present study demonstrated no difference in EVLA, RFA and stripping with regard to eliminating the GSV. The failure rates in the present trial compare well with the rates published in most other studies11,24,25. In the present trial approximately 5 per cent of the GSVs were open and refluxing after 1 year in the stripping and thermoablation groups. A recent meta-analysis described failure rates of 9–28 per cent 1 year after surgery, EVLA, RFA and UGFS25. A higher level of energy in the thermoablation groups, and the use of a flexible wire stripper with a large olive in the stripping group, might have prevented some of the failures26. Still, complications might then have increased, and a higher energy dose than used in the present study is not recommended. Most cases of recanalized or missed GSVs can easily be treated later with UGFS if necessary. With regard to elimination of the GSV in the present study, UGFS was significantly less efficient than the other methods; 16·3 per cent of the GSVs treated with foam were patent and refluxing after 1 year. The protocol allowed one extra sclerotherapy session if the GSV was patent during the first month, and five patients were re-treated accordingly. It is likely, however, that further sessions of sclerotherapy might have reduced the number of failures at 1 year. In addition, it may be speculated that a larger volume than the mean of 8 ml foam per leg used in the present patients might also have improved the results8. Still, as in the case of thermoablation, the risk of complications might then increase. In a recent consensus meeting in Europe, it was recommended not to use volumes of foam above 10 ml per GSV per session27. As the patients are followed, time will show whether the failures represent a relevant clinical problem. Because most of the GSVs in the present study were invisible on ultrasound imaging after 1 year, it is not expected that there will be many cases of recanalization later. Thus, the present findings confirm previous suggestions that all four treatments are efficacious with regard to elimination of the GSV, but that surgery and thermoablation are more efficient than foam.

The recurrent varicose veins seen in this study had minor clinical relevance at 1-year follow-up. The frequency of recurrent varicose veins was not significantly different between the groups. Recurrence is well described after standard surgery but not so much in studies of endovenous ablation. The present study has confirmed previous findings that about 10 per cent of patients may develop new varices within the first year after endovenous ablation28.

Complications were few and mostly minor. Still, one DVT occurred after foam sclerotherapy and one after surgery. Thrombus extension into the common femoral vein has been reported before11, but was not seen in this study. This was probably because the tip of the fibre or catheter was kept 2 cm from the saphenofemoral junction in the thermoablation groups. This distance is currently a generally accepted standard. Because the patients were examined clinically and with ultrasonography at each follow-up visit, relevant complications were unlikely to pass undetected. It is noteworthy that no groin infections were reported in the stripping group. There were significantly more cases of superficial phlebitis in the UGFS and RFA groups; phlebitis is a relatively frequently reported complication of foam sclerotherapy but not so much of RFA8,23. Nevertheless, the phlebitis had little clinical relevance. It is possible that use of 1 per cent polidocanol instead of 3 per cent might have reduced the rate of superficial phlebitis in the foam group without jeopardizing the efficacy of sclerotherapy29.

Although most patients consider postoperative pain after varicose vein treatment acceptable, it is sometimes quite unpleasant and may occasionally be severe. It also influences recovery, including time off work. Patients treated with UGFS and RFA experienced significantly less postoperative pain than those who had laser treatment and conventional surgery, confirming previous observations8,10,22,23. There was no significant difference in efficacy, complications and recovery between the two wavelengths of laser used in the study. EVLA is thought to lead to more postoperative pain than RFA because the laser beam sometimes perforates the vein wall. This may be particularly true when a bare cutting fibre is used. Modification of the fibre tip, by use of a radial emitting fibre in combination with a 1470-nm laser, has been shown to reduce postoperative pain and bruising30.

Return to normal activities and work was influenced by the method of treatment. The shortest time to return was seen in the radiofrequency and foam groups. Easier recovery after RFA, UGFS and EVLA compared with surgery has been reported previously10,31. Although the recovery time was short in patients who had conventional surgery compared with previous findings, the patients treated with endovenous ablation fared even better24. When stripping is performed using ultrasound-guided tumescent anaesthesia the recovery rate might improve. Return to work is influenced by employment and social status as well as the treatment32. These parameters were not examined here, but the fact that time off work and normal activities correlated well in the present study strengthens the conclusion that RFA and UGFS are gentler to the patient than conventional surgery.

The mean VCSS improved similarly in all groups, confirming that all four treatments are efficacious28. Similarly, QoL improved significantly following treatment in all the groups as indicated by the AVVSS and most SF-36® domain scores. Such improvement in QoL after treatment of varicose veins is well known20.

The mean cost per treatment was lowest in the UGFS group and highest in the thermoablation groups. However, the reduced time off work in the endovenous group reduced the total costs compared with surgery. The extra cost of the fibre and catheter in the thermoablation groups was offset by the reduction in time off work. It should be noted, however, that the costs presented here are short term, and it was not possible to estimate the cost of treatment failures that may emerge later. It should also be emphasized that the cost calculations were based on the fixed procedure-related price system and productivity level in Denmark. Thus, the cost comparisons may not apply directly to other countries.

One shortcoming of the present study is that, for practical reasons, the treatment and follow-up examinations were not blinded. However, the patients completed the QoL questionnaires, including drawing new varices on the AVVSS form and recording pain scores, before examination by the surgeon. Furthermore, the patient information sheet was neutral in tone and, as requested by the ethics committee, did not favour any of the treatments. In addition, at 1 year it was most often impossible, on ultrasonography, to see any difference between the groups because the GSV was absent. A further limitation is the variation in technique within the laser group, for example retraction of the laser fibre in pulse mode in 20 patients and treatment of 17 patients with a 980-nm instead of a 1470-nm laser generator. However, subanalysis did not show any difference between the two wavelengths.

The present study was powered to detect a 15 per cent difference in failure rate between the groups as this difference is clinically relevant. Such a significant difference was demonstrated and, accordingly, the present study was a robust comparison of the four treatments.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Julie Serup and Birgit Lawaetz for skilful logistic handling and database management. This study was financed by a grant from the Public Health Insurance Research Foundation of Denmark. Radiofrequency equipment was provided by VNUS Medical Technologies. The authors declare no conflict of interest.