Abstract

Background

Precisely defining the different applications of patient-reported outcome measures (PROs) in clinical practice can be difficult. This is because the intervention is complex and varies amongst different studies in terms of the type of PRO used, how the PRO is fed back, and to whom it is fed back.

Methods

A theory-driven approach is used to describe six different applications of PROs in clinical practice. The evidence for the impact of these applications on the process and outcomes of care are summarised. Possible explanations for the limited impact of PROs on patient management are then discussed and directions for future research are highlighted.

Results

The applications of PROs in clinical practice include screening tools, monitoring tools, as a method of promoting patient-centred care, as a decision aid, as a method of facilitating communication amongst multidisciplinary teams (MDTs), and as a means of monitoring the quality of patient care. Evidence from randomised controlled trials suggests that the use of PROs in clinical practice is valuable in improving the discussion and detection of HRQoL problems but has less of an impact on how clinicians manage patient problems or on subsequent patient outcomes. Many of the reasons for this may lie in the ways in which PROs fit (or do not fit) into the routine ways in which patients and clinicians communicate with each other, how clinicians make decisions, and how healthcare as a whole is organised.

Conclusions

Future research needs to identify ways in with PROs can be better incorporated into the routine care of patients by combining qualitative and quantitative methods and adopting appropriate trial designs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

This paper aims to provide an overview of the different applications of patient-reported outcome measures (PROs) in clinical practice and to summarize the evidence of their impact on the process and outcomes of patient care. The paper has four sections. This introductory section considers some of the difficulties in defining the applications of PROs in clinical practice and highlights the value of a theory-driven approach to understand how and why the feedback of PROs to clinicians might “work”. The section “A taxonomy of applications of PROs in clinical practice” presents a taxonomy and a description of the different applications of using PROs in clinical practice. The section “A summary of the evidence of the impact of PROs on the process and outcomes of care” provides a summary of the evidence relating to the effectiveness of using PROs in clinical practice. The section “Explanations of the impact of PROs in clinical practice and future research” considers some of the explanations of the impact of using PROs in clinical practice on the process and outcomes of care and sets out a number of issues for future research.

Defining the applications of PROs in clinical practice

Two recent systematic reviews of the effectiveness of using PROs identified a general lack of clarity in the intended applications of PROs in clinical practice [1, 2]. Precisely defining the applications of PROs in clinical practice is difficult for several reasons. First, the intervention itself is complex [3]. It aims to change both clinician and patient behaviour with a number of intermediate outcomes needing to be achieved before the more distal outcomes of improvements in patient health status or satisfaction can be realised [4].

Second, the intervention itself is not uniform. Valderas et al. [1] found that trials evaluating the effectiveness of using PROs in clinical practice varied in terms of the type of instrument used, how and when patients completed the PRO, whom the information was fed back to, how often it was fed back to clinicians, whether any training is provided, and the nature of the information that was fed back. They also noted that there was a diversity of outcomes reported within the trials which led to difficulties in summarising the impact of providing PRO feedback to clinicians [1]. This heterogeneity also suggests a lack of consensus amongst researchers regarding what the intervention is and how it is supposed to work.

Greenhalgh et al. [4] argued that bringing clarity to our understanding of the different applications of PROs and their effectiveness requires an explicit theory or set of theories:

-

1

to justify the way in which the intervention is designed and implemented;

-

2

to explain how the intermediate impact of PROs on the process of care might lead to changes in more distal outcomes such as patient health status; and, consequently;

-

3

to identify the most appropriate outcome criteria by which the effectiveness of PROs in clinical practice is judged.

“Theory” here does not necessarily mean recourse to substantive theories proposed by psychology or sociology, though these may be helpful in understanding why one outcome leads to another. Rather, “theory” simply means articulating the causal chain between the intervention and its outcomes [5–7], in order to “delve into the black box” of an intervention. Thus, an “application” of using a PRO in clinical practice represents a clear description (or theory) of how and why its use might lead to outcome A and then to outcome B, etc. Using this approach, the paper will now present a taxonomy of the different applications of using PROs in clinical practice.

A taxonomy of applications of PROs in clinical practice

Table 1 presents a taxonomy of the different applications of PROs in clinical practice along two dimensions. The first dimension describes the level at which the PRO data are aggregated, either at the level of the individual patient or at the group or population level. The second dimension is concerned with whether the application involves the use of PRO data within the clinician patient consultation or not. Some applications may fall into two categories in this dimension. For example, many patients with chronic illness are cared for by a multidisciplinary team. Patients may complete the PRO and this information is then provided to clinicians. The clinicians may discuss the results of the PRO with patients during therapy (thus it is used within the patient–clinician consultation) but may also use the information in multidisciplinary team meetings which occur away from the patient–clinician interface. Furthermore, it is important to note here that “clinician” is not necessarily limited to the medical profession and includes nurses, allied health professionals, social workers, clinical psychologists, psychotherapists, etc. This taxonomy produces four types of application and each could be seen as representing a theory or set of theories to explain how the collection and feedback of PROs to clinicians in clinical practice “works”.

Individual PRO data used at the clinician–patient interface

Screening tools

Much of the literature on the use of PROs in clinical practice has focussed on their use as a screening tool [2, 8, 9]. This application has most frequently been used in screening for depression or anxiety [10, 11] but has also been applied to the detection of problems in physical, social, and emotional functioning [12, 13]. The assumption underlying this application is that depression and functional problems are common in settings such as primary care and secondary care outpatient clinics but often go undetected by clinicians [14–16]. Providing clinicians with patients’ scores on a screening instrument that indicates the possible existence of depression or a functional problem will alert clinicians to this problem; they will then intervene to treat the problem and, consequently, the severity of this problem will decrease [8]. Typically, when PROs are used as screening tools, the patient completes the PRO prior to the consultation and scores are fed back to clinicians on only one occasion; if they are fed back multiple times, clinicians usually only receive the patient’s current score on the PRO.

Monitoring tools

The use of PROs as monitoring tools is perhaps most widely used within psychotherapy, where the approach is known as “patient focussed research” [17–19]. PROs have also been used as monitoring tools in other mental health services [20] and health care more broadly [21]. Common to all these approaches is the desire to answer the question “is this treatment working for this patient”? [22]. The underlying theory of this application is that regular, ongoing feedback of PROs to clinicians will enable both clinicians and patients to reflect on whether the treatment provided is working for the individual patient and, if not, to change the process or content of care accordingly, which will then improve patient outcomes. In psychotherapy, normative data of “expected progress” for patients are also provided to clinicians along with the patient’s current score [19] to assist clinicians in deciding whether changes to treatment are needed.

Patient-centred care

Both the screening and monitoring applications focus on the immediate advantages of using PROs for the clinicians. Recent policy in both the US and UK has emphasised the importance of patient self management and patient involvement in care [23] based on the notions of patient-centred care [24, 25] and shared decision making [26]. In an extension of screening and monitoring applications, the use of PROs in clinical practice may bring the patient’s desired outcomes on to the clinical agenda [27].

PROs that measure issues of importance to patients, such as health-related quality of life (HRQoL), provide a means to alert the clinician to the patient’s concerns about their HRQoL, to clarify the patient’s priorities for care, and to prompt a discussion between patients and clinicians about these issues [2]. This is especially important as patients and doctors do not always agree on which outcomes of care are most important [28]. It is hypothesised that such a discussion could then lead to the patient becoming more involved in decisions about their care and increase the patient’s self-efficacy to manage their own health [29]. This in turn may enable patients to follow their treatment regimens more closely (both because they feel more empowered and their regimens are better suited to their needs) and consequently increase patient satisfaction [30]. Increased collaboration between clinicians and their patients may also address some of the barriers to patient’s appropriate use of primary care [31] or uptake of preventative health services [32].

Group PRO data used at the clinician–patient interface

Decision aids

Group PRO data from clinical trials comparing the outcomes of different treatments may also have a role in facilitating shared decision-making if these data are included in a decision aid. Many of the treatment decisions that patients have to make involve weighing up risks and benefits, sometimes between survival and HRQoL or different aspects of HRQoL [33, 34]. Decision aids are designed to help patients understand treatment options and to clarify their values with regard to these choices as an adjunct to discussions with clinicians [35].

Decision aids usually have three main elements [36]. First, they include descriptions of the treatment procedure and positive and negative consequences of each treatment option. Second, they provide information about the probability of each outcome happening, which is sometimes tailored to the patient’s clinical risk profile. Third, they involve a “values clarification exercise” during which the patient explicitly rates the value to them of the advantages and disadvantages of the different treatment options. Decision aids often include information about the consequences of each treatment option for their symptoms, which have an impact on their HRQoL [37].

Patients want information about the impact of treatment options on their HRQoL when making decisions about treatment [38, 39] and are capable of interpreting HRQoL data when presented in simple formats [40]. When HRQoL data are presented to them in the decision-making process, it has been shown to influence their decisions about treatment options [41]. Thus, group HRQoL data from randomised controlled trials comparing treatment that the patient is making a decision about could be included as part of the description of the consequences of each treatment option in a decision aid.

Individual PRO data away from the clinician–patient interface

Facilitating communication amongst multidisciplinary teams

Patients with chronic illness are increasingly being cared for by multidisciplinary teams (MDTs) in which groups of clinicians from different professions work together to achieve a set of common goals to facilitate patients’ recovery and plan their care [42, 43]. In these contexts, much of the decision making takes place within MDT conferences, away from the clinician–patient interface [44]. Within rehabilitation in particular, PROs have been advocated as a means of providing clinicians with a structured method to document patient’s problems and a way of offering a common language to facilitate communication between professions from different backgrounds [45–47]. This may then overcome some of the challenges posed by multidisciplinary team working, including assisting clinicians to agree on and work towards achieving common treatment goals, to focus on treatment goals that are important to the patient, and to involve patients in setting these goals [48–51]. In this application, the focus is on facilitating communication between different clinicians, whereas the emphasis lies on improving communication between the patient and the clinicians in the application of PROs to promote patient-centred care. In rehabilitation and other multidisciplinary settings, both of these applications of PROs are important.

Group PRO data away from the clinician–patient interface

Evaluating the effectiveness of routine care and assessing the quality of care

PRO data collected for individual patients can also be aggregated at the population level. In the US, Ellwood [52] called for the routine collection of outcome measures for large numbers of patients with similar conditions treated in routine practice. This led to the establishment of patient-outcome research teams (PORTS) to develop databases of routinely collected outcomes data for the purposes of determining the appropriateness and effectiveness of treatments for patients with similar health conditions [53]. For example, the outcomes of patients with similar conditions receiving different interventions can be compared. This approach aims to improve the generalisability of assessments of the effectiveness of treatments, because randomised controlled trials often involve a highly selective sample of patients [54].

The routine collection of PRO data has also been the focus of recent policy initiatives in the UK [55, 56]. It has been suggested that these data could be used to compare the quality of different service providers, to provide the purchasers of care with information to decide which service providers to commission services from and also to enable patients to choose which service provider they wish to be treated by [55, 56]. However, critics argue that there is not a clear link between the PROs and the quality of care, and that case mix adjustment is unsuccessful in removing confounding factors that may explain differences in the health status of patients between different institutions [57–60]. Service commissioners themselves have also expressed concerns about the timeliness and validity of such data and whether variations in patient outcomes can be attributed to differences in the quality of care [61].

A summary of the evidence of the impact of PROs on the process and outcomes of care

How much evidence exists?

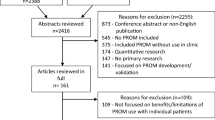

Five systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials evaluating the impact of feeding back individual level PRO data to clinicians have been carried out since 1999 [1, 2, 9, 62, 63]. The most recent review [1] identified 28 studies; the earliest was published in 1978 [64] and the most recent in 2004 [65]. Gilbody et al. [9] and Espallargues et al. [62] used meta analysis to analyse trials using depression or anxiety measures separately from those assessing general health status or HRQoL. Because of the heterogeneity of the outcome criteria used, the other three reviews [1, 2, 63] conducted an overall qualitative analysis of all trials. All of these reviews identified important methodological problems with the studies identified. Most importantly, the method of analysis in the trials did not take into account the method of randomisation. Patients were analysed as if they were the units of randomisation when, in fact, it was clinicians or groups of clinicians that were randomised.

None of the reviews above included the few trials conducted in psychotherapy settings that have assessed ongoing feedback of the clients’ perceptions of the process and outcomes of therapy to therapists [66]. Trials of decision aids have been summarised in two systematic reviews [67, 68] but none of the decision aids within these trials have included HRQoL data extracted from clinical trials comparing two (or more) treatments. Only a small number of non-randomised studies have examined the impact of PROs on multidisciplinary team communication in rehabilitation settings [49–51].

Conceptualising the impact of PROs in clinical practice

The majority of trials of using PROs in clinical practice have not specifically evaluated the effectiveness of the different “applications” as described above. Instead, they have evaluated the impact of using PROs in clinical practice on different process and outcome indicators. These indicators can be conceptualised on a continuum from those most proximal to the clinician–patient encounter, such as effects on clinician–patient communication and problem identification, then intermediate outcomes relating to the patient and clinical decision-making process and most distally to the clinician’s and patient’s management of the health problems, patient’s satisfaction with care, and, finally, eventual health outcomes [4, 69, 70]. Thus, to summarise the evidence for the different applications, evidence relating to the process and outcome indicators most relevant to the particular application are described.

Evidence for screening and monitoring applications

In screening and monitoring applications, outcome criteria relating to the detection and then treatment of problems and then to the patient’s eventual health outcomes are most pertinent. Gilbody et al. [71] found that, for patients who had elevated scores on measures of depression or anxiety (“high risk”), the feedback of these scores to clinicians did increase the rate at which clinicians detected these problems. However, provision of this information did not increase the rate at which clinicians intervened to address these problems, nor did it decrease patient’s depressive symptoms [9].

Studies of the feedback of general health status or HRQoL scores showed a similar pattern of results, with some impact on the detection of problems, but a much smaller impact on how clinicians managed these problems and on subsequent patient outcomes [2, 9, 62, 63]. Valderas et al. [1] identified 14 trials that assessed the impact of feeding back PROs to clinicians on the detection of problems. Of these, 50% of the trials found a significant improvement in the rates of chart notations and diagnoses. However, only 18% of the 11 trials that assessed actions taken found a significant impact of PRO feedback on referrals or additional consultations.

In contrast, evidence from four trials conducted in psychotherapy settings suggests that ongoing monitoring and prediction of treatment failure using PROs specific to psychotherapy improved outcomes for those patients predicted to have poor treatment outcomes [66].

Evidence for the promotion of patient-centred care

Much less is known about the capacity of PROs to promote patient-centred care. This is because few trials have measured outcomes relevant to this application, for example clinician–patient discussion of HRQoL issues, clinician and patient agreement about problems, patients’ involvement in decision making or patient self efficacy. Two more recent trials [65, 70] measured clinician–patient communication using a content analysis of the number of times HRQoL issues were discussed in the consultation (based on tape recordings of consultations). Both found an increase in the number of times HRQoL issues were discussed in the consultation following PRO feedback. Two trials have explored whether the feedback PROs to clinicians increased agreement in patients’ and clinicians’ ratings of the patients’ health status [70, 72] but found limited impact. Two trials explored the impact of PROs on patient adherence to medication [73] or drinking advice [74] but found no effect. Only one third of the thirteen trials that examined the impact of PROs feedback on patient satisfaction found any effect [2]. However, no trials to date have explored the impact of PROs feedback on the clinician–patient relationship, or patient self efficacy.

Evidence for decision aids and multidisciplinary team communication

A recent systematic review of decision aids concluded that they improve knowledge and realistic expectations, enhanced active participation in decision making, lowered decisional conflict and improved agreement between patient values and choice of treatment but had little impact on satisfaction with decision making, anxiety, or health outcomes [67]. A number of decision aids have included descriptions of the impact of treatment options on symptoms [37, 75] and the side-effects of treatment [34] although none has used actual HRQoL data from treatment trials.

Only a small number of non-randomised studies have examined the impact of PROs on multidisciplinary teams working in rehabilitation settings. These have found that the use of PROs did not improve health outcomes for patients but did have a modest benefit on patient satisfaction [49, 50]. Qualitative studies have found that clinicians perceived that the use of a PRO improved client participation in rehabilitation and helped to focus MDT conferences on client needs [51].

Explanations of the impact of PROs in clinical practice and future research

In summary, the evidence suggests that for many of the applications described above, the feedback of PROs to clinicians has a much greater impact on the discussion and detection of patient problems within the consultation than on the ways in which clinicians subsequently manage these problems or on the patient’s eventual health outcomes. Although some have suggested that demonstrating the impact of PRO feedback on doctor–patient communication is sufficient to merit its value [4], others argue that evidence for the broader impact of feeding back PROs to clinicians is needed before clinicians and others can confidently invest resources in this intervention [1]. This raises questions about why these broader impacts have not yet been demonstrated and what needs to be addressed in future research.

The intervention

Greenhalgh et al. [4] offered a number of explanations of these findings relating to both the intervention itself and to the mechanisms through which PRO information may lead to changes in patient care. In terms of the intervention itself, they suggested that using an implementation approach that fostered local ownership, using individualised measures, feeding back the information on multiple occasions, and feeding PRO data back to clinicians other than the medical profession may increase the impact of PROs on decision making. Many of these hypotheses are yet to be tested (or the studies have yet to be published).

The provision of management guidelines, training in the use of PROs, or other means of helping clinicians interpret scores may also facilitate their use by clinicians [12, 76, 77]. However, Valderas et al. [1] were unable to identify specific intervention characteristics that were associated with successful outcomes in their review. There is also a need to take a whole-systems approach to the implementation of PROs in clinical practice. For PROs to be successfully adopted by clinicians, they need to fit into the existing ways in which care is organised and could be used as means or reorganising that care to better meet the needs of patients [78].

Furthermore, instead of focussing exclusively on aspects of the intervention that affect clinical behaviour, we should also consider additional interventions that may support changes to patient behaviour [79]. For example, Ahles et al. [79] supplemented PRO feedback to clinicians with telephone counselling for patients to help them manage their pain and psychosocial problems, and found significant improvements in a number of dimensions of the SF-36 in the intervention group compared with the usual care group.

Clinical and patient behaviour

Greenhalgh et al. [4] also offered a number of reasons why the detection or discussion of HRQoL problems may not translate into changes to the management of these problems. They noted that clinicians or patients may not wish to discuss certain HRQoL topics in the consultation and that clinicians may not view HRQoL problems as being sufficient to change treatment [80–82] Similarly, Gildbody et al. [71] also suggested that clinicians may prefer “watchful waiting” to jumping in to change treatment straight away. Several other studies have highlighted how clinicians prefer to rely on their clinical judgement in making decisions, rather than on information from HRQoL measures [83, 84].

Two recently conducted qualitative studies also provide further support for these ideas. Greenhalgh et al. [85] showed how a multidisciplinary neurorehabilitation team was adept at interpreting information from standardised outcome measures, but used this information as a back up rather than a determinant of their clinical decisions. Another, as yet unpublished, study [86] used conversation analysis to analyse a small sample of tape recorded consultations from a previously conducted trial [65] in which patients with cancer completed the EORTC-QLQC-30 and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADs) and these were fed back to clinicians. This study identified several reasons why discussion of HRQoL problems between clinicians and patients may not lead to changes to treatment. First, the high scores on the PROs sometimes did not reflect a problem that was caused by the disease or its treatment, or this problem was not causing the patient distress and so intervention appeared to be deemed unnecessary. Second, doctors explained to patients that certain problems, particularly fatigue and anxiety, were inevitable side-effects of chemotherapy and consequently treatments were much less likely to be offered for these problems compared with symptoms such as sickness or constipation.

Issues for future research

Many of the reasons why the different applications of using PROs in clinical practice may not influence the management of patients’ problems relate to the ways in which PROs fit (or do not fit) into the routine ways in which patients and clinicians communicate with each other, how clinical decisions are made, and how the healthcare system as a whole is organised. This suggests a need to better tailor the use of PROs to both patients’ and clinicians’ needs and take account of the system within which patient care operates. To address these issues requires the use of qualitative methods to explore how PROs might address patient and clinical views of PRO measures and observe their role in the healthcare system as a whole.

There are also a number of other methodological issues relating to trial design that need to be tackled. Future randomised assessing the applications of using PROs in clinical practice should adopt a theory-driven approach, where the links between the intervention and its intended outcomes should be set out a priori and observed prospectively. This should mean that a smaller number of more appropriate outcome indicators can be selected to judge the effectiveness of PRO feedback, depending on their intended application. Qualitative methods are needed alongside randomised controlled trials to explore how clinicians and patients made sense of and act on PRO information and thus understand the mechanisms through which proximal outcomes do or do not lead to the achievement of more distal outcomes. Finally, trials should adopt designs that incorporate either cluster randomisation or cross-over designs and the method of analysis should take account of the unit of randomisation [87].

References

Valderas, J. M., Kotzeva, A., Espallargues, M., Guyatt, G., Ferrans, C. E., Halyard, M. Y., et al. (2008). The impact of measuring patient-reported outcomes in clinical practice: A systematic review of the literature. Quality of Life Research, 17(2), 179–193. doi:10.1007/s11136-007-9295-0.

Marshall, S., Haywood, K. L., & Fitzpatrick, R. (2006). Impact of patient-reported outcome measures on routine practice: A structured review. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 12(5), 559–568. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2753.2006.00650.x. Review 46 refs.

Campbell, M., Fitzpatrick, R., Haines, A., Kinmonth, A. L., Sandercock, P., Spiegelhalter, D., et al. (2000). Framework for design and evaluation of complex interventions to improve health. British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Ed.), 321(7262), 694–696. doi:10.1136/bmj.321.7262.694.

Greenhalgh, J., Long, A. F., & Flynn, R. (2005). The use of patient-reported outcome measures in routine clinical practice: Lack of impact or lack of theory? Social Science & Medicine, 60(4), 833–843. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.06.022.

Pawson, R. (2002). Does Megan’s law work: A theory-driven systematic review. Report No. 8.

Weiss, C. H. (1995). Nothing as practical as a good theory: Exploring theory-based evaluation for comprehensive community initiatives for children and families. In J. P. Connell (Ed.), New approaches to evaluating community initiatives: Concepts, methods and contexts. Washington, DC: Aspen Institute.

Connell, J. P., & Kubisch, A. C. (1995). Applying a theory of change approach to the evaluation of comprehensive community initiatives: Progress, prospects and problems. In J. P. Connell (Ed.), New approaches to evaluating community initiatives. Washington, DC: Aspen Institute.

Gilbody, S., Whitty, P., Grimshaw, J., & Thomas, R. (2003). Educational and organizational interventions to improve the management of depression in primary care: A systematic review. Journal of American Medical Association, 289(23), 3145–3151. doi:10.1001/jama.289.23.3145.

Gilbody, S. M., Whitty, P. M., Grimshaw, J. M., & Thomas, R. E. (2003). Improving the detection and management of depression in primary care. Quality & Safety in Health Care, 12(2), 149–155. doi:10.1136/qhc.12.2.149.

Dowrick, C. (1995). Does testing for depression influence diagnosis or management by general practitioners? Family Practice, 12(4), 461–465. doi:10.1093/fampra/12.4.461.

Mazonson, P. D., Mathias, S. D., Fifer, S. K., Buesching, D. P., Malek, P., & Patrick, D. L. (1996). The mental health patient profile: Does it change primary care physicians’ practice patterns? The Journal of the American Board of Family Practice, 9(5), 336–345.

Rubenstein, L. V., McCoy, J. M., Cope, D. W., Barrett, P. A., Hirsch, S. H., Messer, K. S., et al. (1995). Improving patient quality of life with feedback to physicians about functional status. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 10(11), 607–614. doi:10.1007/BF02602744.

Rubenstein, L. V., Calkins, D. R., Young, R. T., Cleary, P. D., Fink, A., Kosecoff, J., et al. (1989). Improving patient function: A randomized trial of functional disability screening. Annals of Internal Medicine, 111(10), 836–842.

Marks, J., Goldberg, D., & Hillier, V. F. (1979). Determinants of the ability of general practitioners to detect psychiatric illness. Psychological Medicine, 9, 337–353.

Freeling, P., Rao, B. M., Paykel, E. S., Sireling, L. I., & Burton, R. H. (1985). Unrecognised depression in general practice. British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Ed.), 290(6485), 1880–1883.

Schor, E. L., Lerner, D. J., & Malspeis, S. (1995). Physicians’ assessment of functional health status and well-being. The patient’s perspective. Archives of Internal Medicine, 155(3), 309–314. doi:10.1001/archinte.155.3.309.

Howard, K. I., Moras, K., Bril, l. P. L., Martinovich, Z., & Lutz, W. (1996). Evaluation of psychotherapy. Efficacy, effectiveness, and patient progress. The American Psychologist, 51(10), 1059–1064. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.51.10.1059.

Miller, S. D., Duncan, B. L., & Hubble, M. A. (2007). Beyond integration: The triumph of outcome over process in clinical practice. Psychotherapy in Australia, 10(2), 2–19.

Lambert, M. J., Hansen, N. B., & Finch, A. E. (2001). Patient-focused research: Using patient outcome data to enhance treatment effects. Journal of Consulting Clinical Psychology, 69(2), 159–172. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.69.2.159.

Slade, M. (2002). Routine outcome assessment in mental health services. Psychological Medicine, 32(8), 1339–1343. doi:10.1017/S0033291701004974.

Long, A. F., & Fairfield, G. (1996). Confusion of levels in monitoring outcomes and/or process. Lancet, 347, 1572. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(96)91072-7.

Asay, T. P., Lambert, M. J., Gregersen, A. T., & Goates, M. K. (2002). Using patient-focused research in evaluating treatment outcome in private practice. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58(10), 1213–1225. doi:10.1002/jclp.10107.

Department of Health. (2004). Patient and public involvement in health: The evidence for policy implementation. A summary of the results of the Health in Partnership programme. London: DoH.

Stewart, M. (2001). Towards a global definition of patient-centred care. British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Ed.), 322(7284), 444–445. doi:10.1136/bmj.322.7284.444.

Roter, D. (2000). The enduring and evolving nature of the patient-physician relationship. Patient Education and Counseling, 39(1), 5–15. doi:10.1016/S0738-3991(99)00086-5.

Charles, C., Gafni, A., & Whelan, T. (1997). Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: What does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango). Social Science & Medicine, 44(5), 681–692. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(96)00221-3.

Higginson, I. J., & Carr, A. J. (2001). Measuring quality of life: Using quality of life measures in the clinical setting. British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Ed.), 322(7297), 1297–1300. doi:10.1136/bmj.322.7297.1297.

Rothwell, P. M., McDowell, Z., Wong, C. K., & Dorman, P. J. (1997). Doctors and patients don’t agree: Cross sectional study of patients’ and doctors’ perceptions and assessments of disability in multiple sclerosis. British Medical Journal, 314, 1580–1583.

Long, A. F., & Greenhalgh, J. (1997). Addressing the user’s desired outcomes within routine clinical practice. Journal of Irish College Physicians Surgeons, 26(4), 292–296.

Stimson, G. V. (1974). Obeying doctor’s orders: A view from the other side. Social Science & Medicine, 8(2), 97–104. doi:10.1016/0037-7856(74)90039-0.

Lacy, N. L., Paulman, A., Reuter, M. D., & Lovejoy, B. (2004). Why we don’t come: Patient perceptions on no-shows. Annals of Family Medicine, 2(6), 541–545. doi:10.1370/afm.123.

Ling, B. S., Klein, W. M., & Dang, Q. (2006). Relationship of communication and information measures to colorectal cancer screening utilization: Results from HINTS. Journal of Health Communication, 11(Suppl 1), 181–190. doi:10.1080/10810730600639190.

O’Connor, A. (2001). Using patient decision aids to promote evidence-based decision making. ACP Journal of Club, 135(1), A11–A12.

Sawka, C. A., Goel, V., Mahut, C. A., Taylor, G. A., Thiel, E. C., O’Connor, A. M., et al. (1998). Development of a patient decision aid for choice of surgical treatment for breast cancer. Health Expect, 1(1), 23–36. doi:10.1046/j.1369-6513.1998.00003.x.

O’Connor, A. M. (2007). Using decision aids to help patients navigate the “grey zone” of medical decision making. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 176(11), 1597–1598. doi:10.1503/cmaj.070490.

Elwyn, G., O’Connor, A., Stacey, D., Volk, R., Edwards, A., Coulter, A., et al. (2006). Developing a quality criteria framework for patient decision aids: Online international Delphi consensus process. British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Ed.), 333(7565), 417. doi:10.1136/bmj.38926.629329.AE.

Feldman-Stewart, D., Brundage, M. D., Van, M. L., & Svenson, O. (2004). Patient-focussed decision-making in early-stage prostate cancer: Insights from a cognitively based decision aid. Health Expect, 7(2), 126–141. doi:10.1111/j.1369-7625.2004.00271.x.

Feldman-Stewart, D., Brundage, M. D., Hayter, C., Groome, P., Nickel, J. C., Downes, H., et al. (2000). What questions do patients with curable prostate cancer want answered? Medical Decision Making, 20(1), 7–19. doi:10.1177/0272989X0002000102.

Brundage, M., Leis, A., Bezjak, A., Feldman-Stewart, D., Degner, L., Velji, K., et al. (2003). Cancer patients’ preferences for communicating clinical trial quality of life information: A qualitative study. Quality of Life Research, 12(4), 395–404. doi:10.1023/A:1023404731041.

Brundage, M., Feldman-Stewart, D., Leis, A., Bezjak, A., Degner, L., Velji, K., et al. (2005). Communicating quality of life information to cancer patients: A study of six presentation formats. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 23(28), 6949–6956. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.12.514.

Brundage, M., Feldman-Stewart, D., Leis, A., Bezjak, A., & Pater, J. L. (2006). Patients’ judgements about the value of quality of life information when considering lung cancer (NSCLC) treatment options. International Society for Quality of Life Research meeting abstracts. The QLR Journal A-68, Abstract no. 1810.

Payne, M. (2000). Teamwork in multiprofessional care. Basingstoke: Macmillan.

Davis, R. M., Wagner, E. G., & Groves, T. (2000). Advances in managing chronic disease: research, performance measurement and quality improvement are key. British Medical Journal, 320, 525–526. doi:10.1136/bmj.320.7234.525.

Heruti, R. J., & Ohry, A. (1995). The rehabilitation team. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 74(6), 466–468. doi:10.1097/00002060-199511000-00017.

van Bennekom, C. A., Jelles, F., & Lankhorst, G. J. (1995). Rehabilitation activities profile: The ICIDH as a framework for a problem-oriented assessment method in rehabilitation medicine. Disability and Rehabilitation, 17(3–4), 169–175.

Law, M., Polatajko, H., Pollock, N., McColl, M. A., Carswell, A., Baptiste, S., et al. (1994). Pilot testing of the Canadian occupational performance measure: Clinical and measurement issues. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 61(4), 191–197.

Callahan, M. B. (2001). Using quality of life measurement to enhance interdisciplinary collaboration. Advances in Renal Replacement Therapy, 8(2), 148–151. doi:10.1053/jarr.2001.24248.

Verhoef, J., Toussaint, P. J., Vliet Vlieland, T. P., & Zwetsloot-Schonk, J. H. (2004). The impact of structuring multidisciplinary team conferences mediated by ICT in the treatment of patients with rheumatic diseases. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics, 103, 183–190.

Verhoef, J., Toussaint, P. J., Zwetsloot-Schonk, J. H., Breedveld, F. C., Putter, H., & Vlieland, T. P. M. V. (2007). Effectiveness of the introduction of an international classification of functioning, disability and health-based rehabilitation tool in multidisciplinary team care in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis and Rheumatism, 57(2), 240–248. doi:10.1002/art.22539.

Beckerman, H., Roelofsen, E., Knol, D., & Lankhorst, G. (2004). The value of the rehabilitation activities profile (RAP) as a quality sub-system in rehabilitation medicine. Disability and Rehabilitation, 26(7), 387–400. doi:10.1080/09638280410001662941.

Wressle, E., Lindstrand, J., Neher, M., Marcusson, J., & Henriksson, C. (2003). The Canadian occupational performance measure as an outcome measure and team tool in a day treatment programme. Disability and Rehabilitation, 25(10), 497–506. doi:10.1080/0963828031000090560.

Ellwood, P. M. (1998). Shattuck lecture—outcomes management. A technology of patient experience. New England Journal of Medicine, 318, 1549–1556.

Wennberg, J. E., Barry, M. J., Fowler, F. J., & Mulley, A. (1993). Outcomes research, PORTs, and health care reform. Annals of New York Academy of Sciences, 703, 52–62. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb26335.x.

Gilbody, S. M., House, A. O., & Sheldon, T. A. (2002). Outcomes research in mental health. Systematic review. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 181, 8–16. doi:10.1192/bjp.181.1.8.

Department of Health. (2008). High quality care for all: NHS next stage review final report. London: Department of Health.

Appleby, J., & Devlin, N. (2004). Measuring success in the NHS: Using patient assessed health outcomes to manage performance of healthcare providers. London: Dr. Foster Ethics Committee.

Gompertz, P., Pound, P., Briffa, J., & Ebrahim, S. (1995). How useful are non-random comparisons of outcomes and quality of care in purchasing hospital stroke services. Age and Ageing, 24(2), 127–141. doi:10.1093/ageing/24.2.137.

Lilford, R. J., Brown, C. A., & Nicholl, J. (2007). Use of process measures to monitor the quality of clinical practice. British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Ed.), 335(7621), 648–650. doi:10.1136/bmj.39317.641296.AD.

Davies, H. T. O., & Combie, I. K. (1997). Interpreting health outcomes. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 3(3), 187–199. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2753.1997.00003.x.

Browne, J., Jamieson, L., Lewsey, J., van der, M. J., Copley, L., & Black, N. (2008). Case-mix & patients’ reports of outcome in independent sector treatment centres: Comparison with NHS providers. BMC Health Services Research, 8, 78. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-8-78.

McColl, A., Rodrick, P., Gabbay, J., & Ferris, G. (1998). What do health authorities think of population based health outcome indicators? Quality in Health Care, 7, 90–97.

Espallargues, M., Valderas, J. M., & Alonso, J. (2000). Provision of feedback on perceived health status to health care professionals: A systematic review of its impact. Medical Care, 38(2), 175–186. doi:10.1097/00005650-200002000-00007.

Greenhalgh, J., & Meadows, K. (1999). The effectiveness of the use of patient-based measures of health in routine practice in improving the process and outcomes of patient care: A literature review. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 5(4), 401–416. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2753.1999.00209.x.

Moore, J. T., Silimperi, D. R., & Bobula, J. A. (1978). Recognition of depression by family medicine residents: The impact of screening. The Journal of Family Medicine, 7, 509–513.

Velikova, G., Booth, L., Smith, A. B., Brown, P., Lynch, P., Brown, J. M., et al. (2004). Measuring quality of life in routine oncology practice improves communication and patient well being—a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 22(4), 714–724. doi:10.1200/JCO.2004.06.078.

Lambert, M. J., Harmon, C., Slade, K., Whipple, J. L., & Hawkins, E. J. (2005). Providing feedback to psychotherapists on their patients’ progress: Clinical results and practice suggestions. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61(2), 165–174. doi:10.1002/jclp.20113.

O’Connor, A. M. (2007). Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Online: Update Software), 4.

Bekker, H. L., Thornton, J. G., Airey, M., Connelly, J., Hewison, J., Robinson, M., et al. (1999). Informed decision making: an annotated bibliography and systematic review. Health Technology Assessment, 3(1), 1–156.

Valderas, J. M., Rue, M., Guyatt, G., & Alonso, J. (2005). The impact of the VF-14 index, a perceived visual function measure, in the routine management of cataract patients. Quality of Life Research, 14, 1743–1753. doi:10.1007/s11136-005-1745-y.

Detmar, S. B., Muller, M. J., Schornagel, J. H., Wever, L. D., & Aaronson, N. K. (2002). Health related quality of life assessments and patient-physician communication. Journal of American Medical Association, 288(23), 3027–3034. doi:10.1001/jama.288.23.3027.

Gilbody, S. M., House, A. O., & Sheldon, T. A. (2001). Routinely administered questionnaires for depression and anxiety: Systematic review. British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Ed.), 322(7283), 406–409. doi:10.1136/bmj.322.7283.406.

Wasson, J., Hays, R., Rubenstein, L., Nelson, E., Leaning, J., Johnson, D., et al. (1992). The short-term effect of patient health status assessment in a health maintenance organization. Quality of Life Research, 1(2), 99–106. doi:10.1007/BF00439717.

Kazis, L., Callahan, L., Meenan, R., & Pincus, T. (1990). Health status reports in the care of patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 43(11), 1243–1253. doi:10.1016/0895-4356(90)90025-K.

Saitz, R., Horton, N. J., Sullivan, L. M., Moskowitz, M. A., & Samet, J. H. (2003). Addressing alcohol problems in primary care: A cluster randomized, controlled trial of a systems intervention. The screening and intervention in primary care (SIP) study. Annals of Internal Medicine, 138(5), 372–382.

Murray, E., Davis, H., See Tai, S., Coulter, A., Gray, A., & Haines, A. (2001). Randomised controlled trial of sn interactive multimedia decision aid on benign prostatic hypertrophy in primary care. British Medical Journal, 323, 1–6. doi:10.1136/bmj.323.7303.1.

Mathias, S. D., Fifer, S. K., Mazonson, P. D., Lubeck, D. P., Buesching, D. P., & Patrick, D. L. (1994). Necessary but not sufficient: The effect of screening and feedback on outcomes of primary care patients with untreated anxiety. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 9(11), 606–615. doi:10.1007/BF02600303.

Magruder-Habib, K., Zung, W. W. K., & Feussner, J. R. (1990). Improving physicians’ recognition and treatment of depression in general medical care. Results from a randomized clinical trial. Medical Care, 28, 239–250. doi:10.1097/00005650-199003000-00004.

Donaldson, M. S. (2008). Taking PROs and patient-centred care seriously: Incremental and disruptive ideas for incorporating PROs in oncology practice. Quality of Life Research. doi:10.1007/s11136-008-9414-6.

Ahles, T. A., Wasson, J. H., Seville, J. L., Johnson, D. J., Cole, B. F., Hanscom, B., et al. (2006). A controlled trial of methods for managing pain in primary care patients with or without co-occurring psychosocial problems. Annals of Family Medicine, 4(4), 341–350. doi:10.1370/afm.527.

Detmar, S. B., Muller, M. J., Wever, L. D., Schornagel, J. H., & Aaronson, N. K. (2001). The patient-physician relationship. Patient-physician communication during outpatient palliative treatment visits: An observational study. Journal of American Medical Association, 285(10), 1351–1357. doi:10.1001/jama.285.10.1351.

Detmar, S. B., Aaronson, N. K., Wever, L. D., Muller, M. J., & Schornagel, J. H. (2000). How are you feeling? Who wants to know? Patients’ and oncologists’ preferences for discussing health related quality of life issues. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 18(18), 3295–3301.

Detmar, S. B., Muller, M. J., Schornagel, J. H., Wever, L. D., & Aaronson, N. K. (2002). Role of health-related quality of life in palliative chemotherapy treatment decisions. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 20(4), 1056–1062. doi:10.1200/JCO.20.4.1056.

Gilbody, S. M., House, A. O., & Sheldon, T. A. (2002). Psychiatrists in the UK do not use outcomes measures. National survey. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 180, 101–103. doi:10.1192/bjp.180.2.101.

McKevitt, C., & Wolfe, C. (2002). Quality of life: what, how, why? Quality in aging-policy. Practice and Research, 3(1), 13–19.

Greenhalgh, J., Flynn, R., Long, A. F., & Tyson, S. (2008). Tacit and encoded knowledge in the use of standardised outcome measures in multidisciplinary team decision making: A case study of in-patient neurorehabilitation. Social Science & Medicine, 67, 183–194. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.006.

Greenhalgh, J., Abhyankar, P., McCluskey, S., Takeurchi, E., & Velikova, G. (2008). How do doctors and patients talk about QoL data in consultations? International Society for Quality of Life Research meeting abstracts. The QLR Journal A-16. Abstract no. 1348.

Fayers, P. M. (2008). Evaluating the effectiveness of using PROs in clinical practice: a role for cluster-randomised trials. Quality of Life Research. doi:10.1007/s11136-008-9391-9.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Greenhalgh, J. The applications of PROs in clinical practice: what are they, do they work, and why?. Qual Life Res 18, 115–123 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-008-9430-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-008-9430-6